You are listening to the audio introduction to the world premiere of the new opera We Are The Lucky Ones by composer Philip Venables, director and librettist Ted Huffman, and librettist Nina Segal. My name is Laura Roling, I am a dramaturge at Dutch National Opera, and I’ll give you a brief overview to prepare you for your opera visit. We Are The Lucky Ones is a remarkable new opera with great ambition.

This opera doesn’t tell the story of a few individuals, as so many operas do, but instead tries to capture the story of an entire generation. Specifically, the generation born in Western Europe in the 1940s. What makes this generation so special? These people were born during or just after the Second World War, they were children during the post-war reconstruction, a time of great scarcity, when much of Europe still lay in ruins.

But what this generation experienced in their lifetimes after such a difficult start is unprecedented in human history: explosive economic growth, the development of the welfare state, far-reaching technological advances like smartphones and the internet, increasing globalisation, and changing social structures. Of course, life didn’t improve equally for every individual within this generation.

Inequality, after all, still hasn’t been eradicated. The circumstances of your birth can still influence your life for better or worse, but if you zoom out and look at the bigger picture, it’s fair to say that inequality across Western Europe has significantly decreased since 1945. Almost everyone in this generation ended up better off than their parents and grandparents.

They had more opportunities to pursue education, to buy a house, perhaps even one or more cars, to travel further, to fly eventually. And you can rightly say that this generation is one of lucky ones, of people who have had good fortune. But the level of progress seen within a single lifetime will most likely not be matched by this generation’s children and grandchildren.

The economy won’t grow as explosively again. Let alone the current geopolitical climate and the effects of the climate crisis that now threaten us. But how does this generation look back on their lives? What were the defining moments? What do they regret? What kind of world are they leaving behind? And how do they reflect on that themselves? These were the questions that fascinated the artistic team of We Are The Lucky Ones.

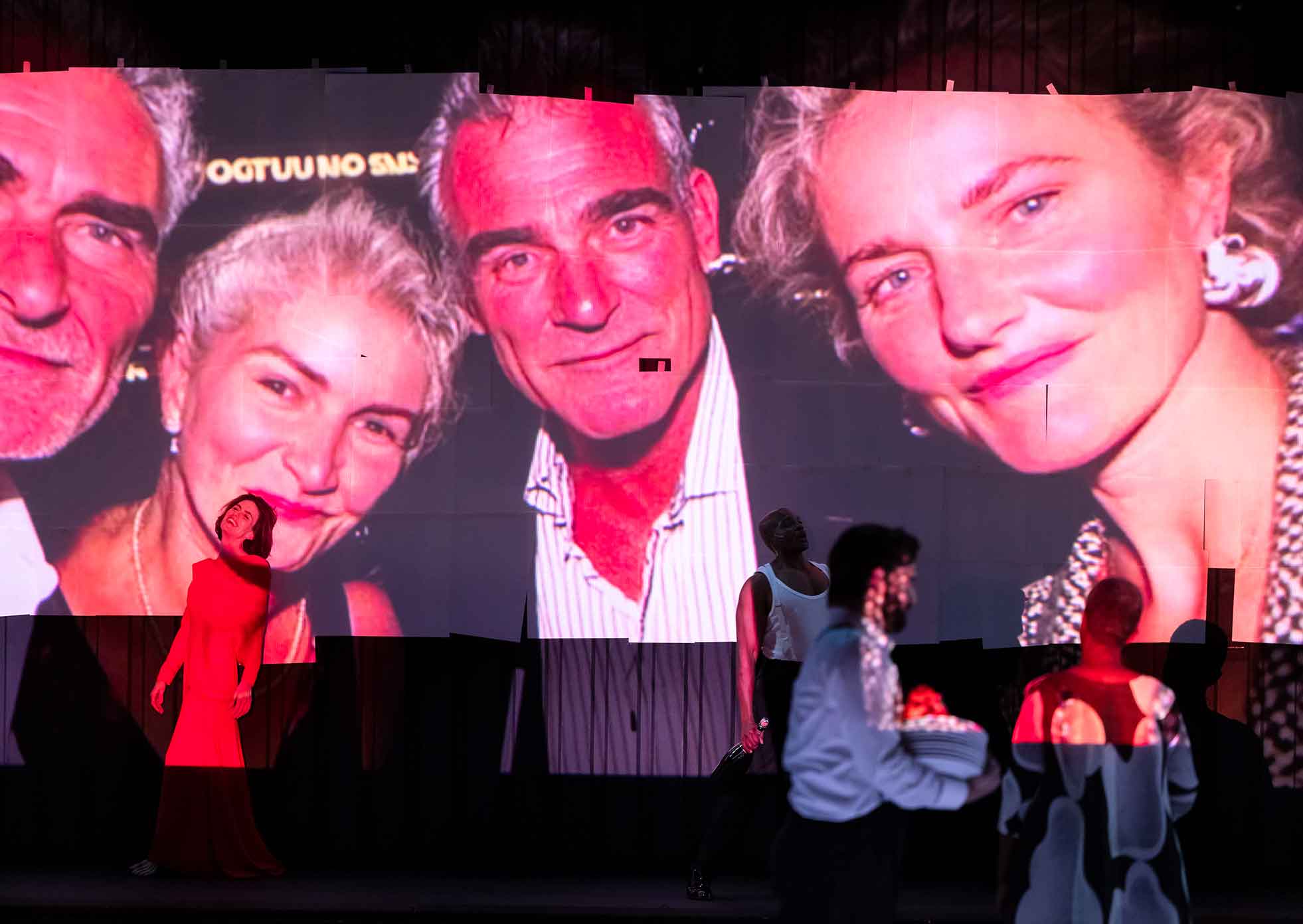

To answer these questions, composer Philip Venables and librettists Ted Huffman and Nina Segal didn’t just turn to their own imaginations. Instead, they chose to appoint a team of no fewer than six researchers from different language backgrounds. These researchers spoke with around eighty people born in the 1940s. The interviewees lived in the Netherlands, Belgium, the United Kingdom, France, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, the Faroe Islands and Iceland.

One interviewee was from the United States, but it was soon decided to focus entirely on Western Europe. Quite a long list of countries. Based on a set of questions, the interviewees spoke about their work, important purchases, people they loved, trips they had taken, and things they regretted.

They were also asked about their view of the future, which wasn’t always optimistic. These interviews were transcribed and translated and passed on to the English-speaking artistic team.

Their task was to process an overwhelming stack of roughly 350 pages of interview transcripts. They read through them thoroughly, looking for recurring threads and central themes, and they also noted striking turns of phrase and word choices.

Among the interviews were a few remarkable personal stories. One interviewee, for example, had been involved in a knife fight on a beach in Vietnam. But composer Philip Venables and librettists Ted Huffman and Nina Segal deliberately set aside those kinds of exciting, exceptional stories.

What they were looking for were not the exceptions, but the shared experiences, the tendencies, the averages. In this way, they arrived at a broader, collective history of a generation. The libretto took the shape of a collage—a mosaic of more than sixty different memories and experiences, arranged chronologically from 1940 to the present day.

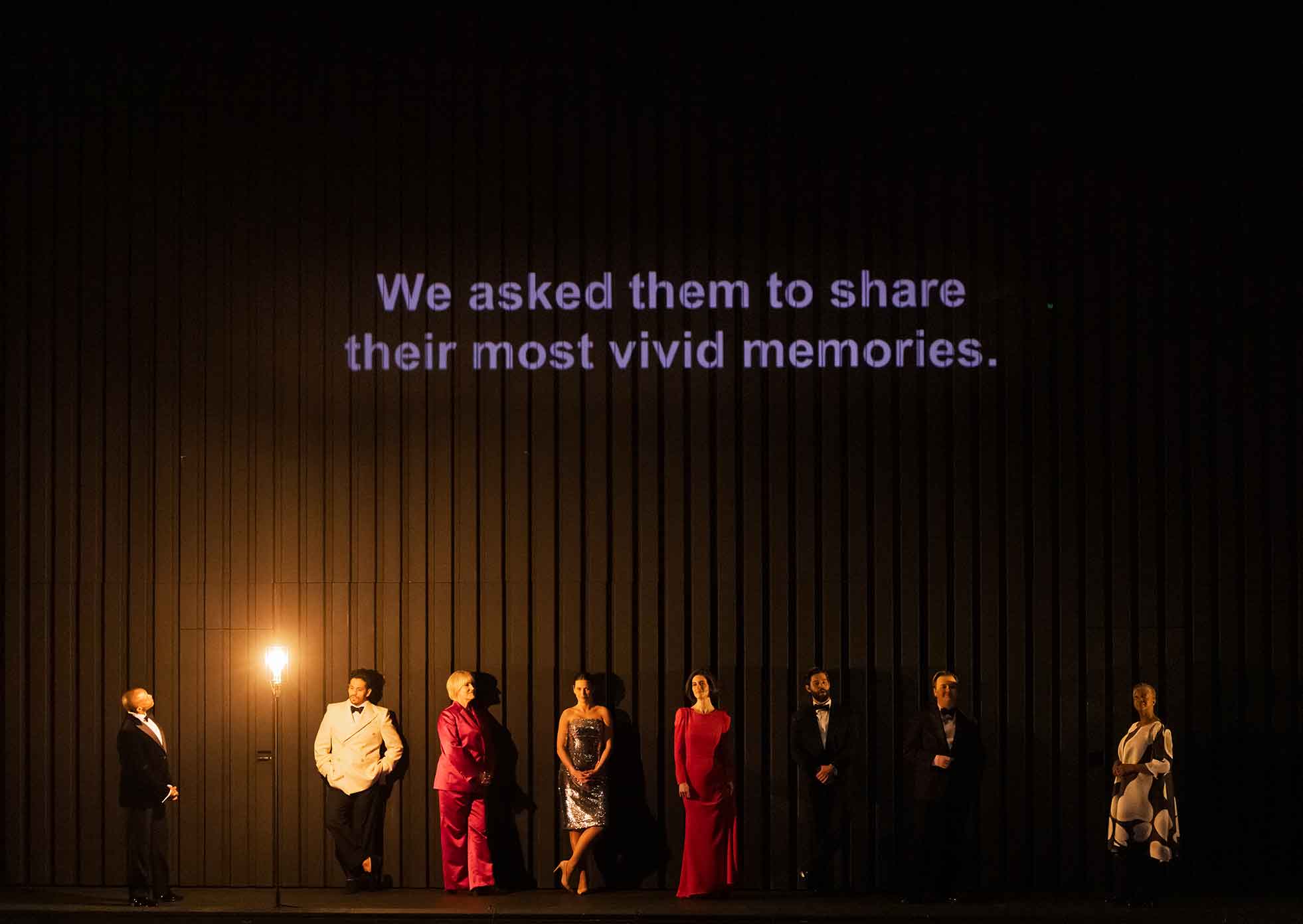

We Are The Lucky Ones is an opera for eight singers, whose roles are simply numbered from one to eight. The performers don’t portray individual or clearly defined characters from beginning to end. Instead, in each scene—there are about sixty of them—they evoke the memory of a different person.

As vessels for the interviewees’ voices, they figuratively put on a new mask each time. Sometimes the pairing between a singer and the memory they express feels very natural and intuitive, but at other times the artistic team deliberately emphasises the contrast between the performer and the voice or story being heard. A striking example is the scene in which a tenor briefly embodies an East German single mother.

She talks about her worries in 1989 regarding her future in the capitalist West. Alongside solo scenes, the opera also includes moments of dynamic collective storytelling. A strong example is the scene in which a tenor recalls eating his first orange. As he speaks, the other seven singers from the ensemble take on the voice of his mother in unison, explaining to her child how to peel an orange.

The music is sweet and sultry—until the orange turns out to taste sour. Philip Venables’ composition draws heavily on the music of the 1940s and ’50s—the music this generation would have heard in their youth. Swing, old Hollywood influences and big band, with lots of brass and percussion. The opera also features a lot of dance music, and there is plenty of movement on stage. For example, when the ensemble sings a passionate waltz about how lucky they are to still be healthy and happily married in middle age.

We Are The Lucky Ones takes the audience through this generation’s memories—from their early childhood to old age. Sometimes the memories are personal, sometimes they are connected to major political events.

In addition to the sung memories, you will hear spoken, reflective texts in which the interviewees’ answers to the question about the future take centre stage. One big question is whether the people who were interviewed and attend the opera will recognise themselves in the performance. Perhaps they will—after all, the libretto draws directly from the interviews conducted with them, from their words and experiences.

But it’s just as possible that they won’t. The artistic team deliberately chose to highlight the common denominators—the things that are not striking or highly individual. And there was a certain distance in the creative process between the interviewees and the artistic team.

The team worked with translations of transcripts of conversations they hadn’t conducted themselves. And the memories shared by the interviewees are, by definition, subjective. Everyone shapes their life story when they tell it.

In this way, something has emerged from real input and real stories that is both authentic and artificial. The line between truth and fiction in this opera is deliberately blurred. What comes directly from the interviews? What has been selected, edited or even transformed by the makers to reflect their own vision of this generation? Thank you for listening to this introduction.

If you’d like to know more about the opera, you can read the programme book in the theatre or online. And 45 minutes before the performance, you’re welcome to attend a more extensive introduction in the theatre. Enjoy the performance.