Oum – A Son’s Quest for His Mother

Performance information

- Performance information

- In a nutshell

- The story

- Timeline for Oum Kalthoum and Wajdi Mouawad

- Interview with Bushra El-Turk, Kenza Koutchoukali and Wout van Tongeren

- Background: the legacy of Oum Kalthoum

- Background: about writer Wajdi Mouawad and his work

- Biographies artistic team

- Biographies singers

Performance information

Voorstellingsinformatie

Performance information

Oum – A Son’s Quest for His Mother

Bushra El-Turk / Wajdi Mouawad / Kenza Koutchoukali

Duration

Approx. 90 minutes

This performance is sung and spoken in English and Arabic, with surtitles in Dutch and English.

Dutch translation surtitles Karim Ameur (spoken texts) and the Dramaturgy Department of Dutch National Opera (sung texts)

Libretto

Wout van Tongeren, based on the play Un obus dans le coeur and fragments from the novel Visage retrouvé by Wajdi Mouawad, in the English translation by Linda Gaboriau

World premiere

20 March 2025

Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam

Musical direction

Kanako Abe

Stage direction and concept

Kenza Koutchoukali

Set and video design

Yannick Verweij

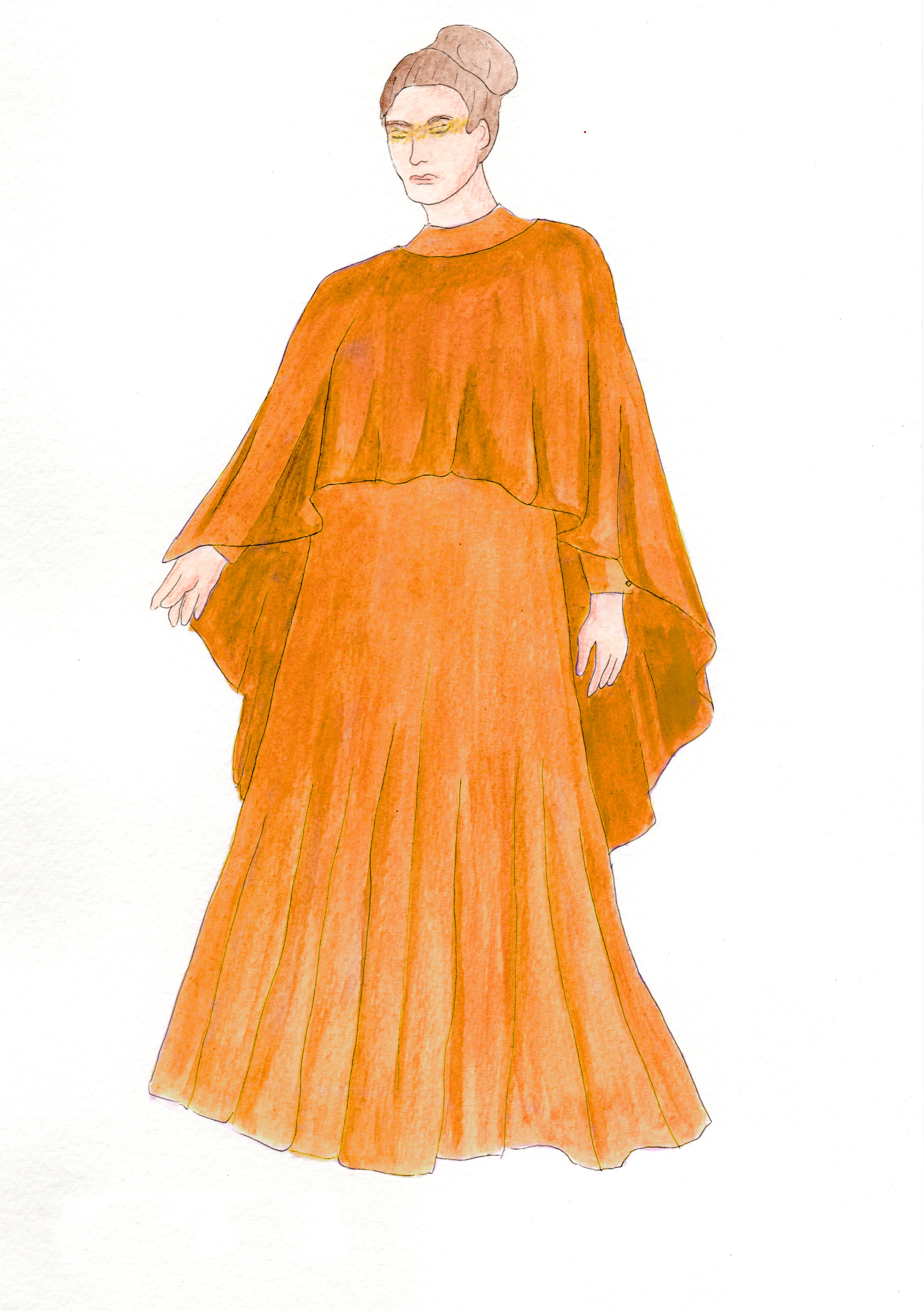

Costume design

Hannah Sibai

Lighting design

Yuri Schreuders

Choreography

Roshanak Morrowatian

Dramaturgy

Wout van Tongeren

Wahab (actor)

Nadia Amin

Contralto

Ghalia Benali

Mezzo-soprano

Dima Orsho

Soprano

Bernadeta Astar

Orchestra

Amsterdams Andalusisch Orkest

Musical project leader Amsterdams Andalusisch Orkest

Elias El Houssaini

The song “Al-Atlal” by Oum Kalthoum was composed by Riad Al Sunbati on lyrics composed from poems by Ibrahim Nagi.

The video design includes photos taken by Maryam Touzani

Production team

Assistant director and evening director

Nico Weggemans

Trainee directing

Meia Oei

Assistant video-design

Joske Commandeur

Repetitors

Samir Bendimered

Irina Sisoyeva

Language coach

Peter Lockwood

Stage managers

Marjolein Bergsma

Marie-José Litjens

Niek Stroomer

Artistic planning

Sonja Heyl

Master Carpenter

Peter Brem

Lighting manager

Coen van der Hoeven

Props crewman

Niko Groot

Set supervision

Valerie Smalen

Costume supervision

Lars Willhausen

Senior dresser

Jazmin Blaton

Senior make-up artist

Carlijn Spee

Sound engineer

Ramón Schoones

Co-producers

Amsterdams Andalusisch Orkest

Creative director

Mohamed Aadroun

Business director

Eva Hermus

Meervaart

Director Yassine Boussaid

Artistic coordinator Christiaan Mooij

Amsterdams Andalusisch Orkest

Violin

Elias El Houssaini

Mohamed Al Mokhlis

Viola

Jaafar Lougmani

Cello

Léa Besançon

Double bass

Rémy Dielemans

Ney and flute

Marianne Noordink

Qanûn

Ahmed El Maai

Ud

Haytham Safia

Timpani

Modar Salama

Duduk, kaval, recorder and crumhorn

Raphaela Danksagmüller (also associated with Ensemble Zar)

Kamanche, ghichak, violin and viola

Faraz Eshghi Sahraei (also associated with Ensemble Zar)

Accordeon

Bartosz Głowacki (also associated with Ensemble Zar)

In a nutshell

About the creators of Oum – A Son’s Quest for His Mother and their musical inspiration Oum Kalthoum as well as about the writer of the story, Wajdi Mouawad.

In het kort

Bushra El-Turk and Kenza Koutchoukali

Oum – A Son’s Quest for His Mother marks the first collaboration between composer Bushra El-Turk and director Kenza Koutchoukali. El-Turk has received multiple awards for her previous opera, Woman at Point Zero, which premiered in Aix-en-Provence before being performed at venues including The Royal Opera (London), Vienna Festival, and the Seoul Performing Arts Festival. Koutchoukali has played a key role in developing new operas at institutions such as the Dutch National Opera and the Vienna State Opera. For both artists, Oum – A Son’s Quest for His Mother is a project that resonates with their personal histories, as Western European artists with roots in North Africa and the Middle East.

The inspiring music of Oum Kalthoum

The Egyptian singer Oum Kalthoum is undoubtedly one of the most celebrated artists in the Middle East and North Africa; the love for her songs transcends generations, social classes, and ethnic groups. Fifty years after her passing, Oum Kalthoum’s music remains as vibrant as ever, including in Western European cities like Amsterdam, where her voice echoes through countless living rooms, shops, and cars. In recent years, her work has been performed increasingly in the city’s concert halls and theatres, thanks in part to the efforts of the Amsterdam Andalusian Orchestra and Meervaart. With Oum – A Son’s Quest for His Mother, they join forces with the Dutch National Opera to present a music-theatre production inspired by the musical universe of Oum Kalthoum, right in the heart of Amsterdam

A story by Wajdi Mouawad

In his debut novel Visage retrouvé, Lebanese-Canadian writer and theatre maker Wajdi Mouawad explores the troubled relationship between a son and his mother. Elements of Mouawad’s personal history can be recognized in the novel: the protagonist flees a war-torn country with his family and struggles to find his place – both within his family and in his new homeland – until art ultimately offers him salvation. Mouawad himself adapted his novel into a theatrical monologue, which, along with selected passages from the book, forms the foundation of the libretto for the music-theatre production Oum – A Son’s Quest for His Mother. The title Oum refers both to the musical inspiration, Oum Kalthoum, and to the story itself: ‘oum’ is the Arabic word for mother.

Al-Atlal

Composer Bushra El-Turk and director Kenza Koutchoukali decided to connect Wajdi Mouawad’s story with one of Oum Kalthoum’s most famous songs: ‘Al-Atlal’ (The Ruins). The lyrics of this song, composed from two poems by Ibrahim Nagi, were set to music by Riad Al Sunbati. ‘Al-Atlal’ laments a lost love, but its rich imagery and multiple layers of meaning allow for much broader interpretations. Beneath the song’s melancholy lies a deep resilience – the ability to find beauty and meaning in the fractures of existence. Bushra El-Turk wove the song into her composition, where elements of ‘Al-Atlal’ can be heard almost continuously— sometimes clearly recognizable, at other times barely perceptible. In the production’s climax, the song is performed (almost) in its entirety.

The story

A winter’s night in a city somewhere in the Western world. Wahab, a nineteen-year-old boy, is struggling through a snowstorm, on his way to the hospital where his mother is on her deathbed ...

The story

A winter’s night in a city somewhere in the Western world. Wahab, a nineteen-year-old boy, is struggling through a snowstorm, on his way to the hospital where his mother is on her deathbed. His head is spinning: is it too late to turn around? Why isn’t he crying? How did his relationship with his mother become so complicated?

Wahab remembers his fourteenth birthday, the day on which he discovered his mother’s face had changed all of a sudden. No one else noticed; Wahab was the only person who no longer recognised her. Other episodes from his childhood run through his mind. It gradually becomes clear to him that this trip to see his dying mother will also be a confrontation with a haunting memory from the distant past, an awful event in the country of his birth that he witnessed as a seven-year-old.

On his way to his mother, Wahab carries the song Al-Atlal (‘The ruins’) by the Egyptian singer Oum Kalthoum deep in his heart. The song encapsulates the grief of losing your home, longing for love and ultimately the hope for reconciliation amidst the debris of a broken relationship.

Timeline

From the early years of Oum Kalthoum's life to the publication of Wajdi Mouawad's debut novel Visage retrouvé in 2002.

Timeline

Approx. 1898-1904

Oum Kalthoum is born in Tamay Ez-Zahayra, a village in the middle of the Nile Delta. Her father is a local imam who earns income on the side by singing religious songs during festivities. He did this initially with his son, but when Oum Kalthoum turns out even at a young age to have an exceptionally beautiful singing voice, she is soon included in the family group.

Approx. 1915

Her voice comes to the attention of people from the professional music world. While still a teenager she is increasingly invited to give performances, through which she helps support her family.

Approx. 1923

After several visits to Cairo, Oum Kalthoum’s family settle there for good. The city is starting to flourish culturally in the aftermath of the Egyptian revolution in 1919, which led to partial independence from the United Kingdom. Cairo becomes the cultural centre of the Arab world.

1934

Oum Kalthoum, now an established performer known throughout the Arabic-speaking world, gives the first broadcast of the newly founded Radio Cairo. From then on, she sings a concert for the radio station every first Thursday of the month. The streets of Cairo are almost deserted during these programmes as everyone gathers around the radio to listen — which gives the concerts a legendary status. In the years that follow, Oum Kalthoum becomes a film star too, acting in various Egyptian films.

1952

The military coup in 1952 leads to the fall of the Egyptian royal family and complete independence from Britain. Oum Kalthoum is on good terms with Gamal Abdel Nasser, who becomes president of the recently founded Republic of Egypt in 1956.

Increasingly, she places her music in a political context. Nasser in turn takes advantage of Oum Kalthoum’s popularity: his radio speeches are often tactically scheduled close to Oum Kalthoum’s broadcasts.

1967

In the Six Day War of June 1967, Egypt suffers a humiliating defeat at the hands of Israel. In the aftermath, Oum Kalthoum organises benefit concerts in various Arabic countries to raise money to rebuild the Egyptian army. She often performs Al-Atlal, a song she had released one year before the war. It becomes a major hit in the Middle East.

One year after the war, in 1968, the author Wajdi Mouawad is born in Lebanon.

1975

Oum Kalthoum dies on 3 February 1975. Some four million people allegedly line the streets of Cairo on the occasion of her funeral. Two months later, civil war breaks out in Lebanon. One of the main catalysts is Black Sunday, when a series of violent conflicts between armed groups ends up in a bloodbath on 17 April when the people on a bus returning from a Palestinian political meeting are murdered by a Phalangist militia (a right-wing Christian group).

About one million Lebanese flee the country during the civil war (which ends in 1990). They include ten-year-old Wajdi Mouawad and his family, and the parents of the composer Bushra El-Turk.

2002

Wajdi Mouawad’s family ends up via France in Montreal, Canada, in 1983. Mouawad attends the theatre school and develops into a director and writer/playwright. In 2002, he publishes his debut novel Visage retrouvé, based partly on his own childhood memories. The production Oum – A Son’s Quest for his Mother is based on this novel and Mouawad’s own subsequent adaptation for the stage.

Interview with Bushra El-Turk, Kenza Koutchoukali and Wout van Tongeren

Composer Bushra El-Turk, director Kenza Koutchoukali and dramaturg and librettist Wout van Tongeren jointly developed the concept for Oum – A Son’s Quest for His Mother. During the second week of rehearsals, the makers reflect on their new creation.

Interview with Bushra El-Turk, Kenza Koutchoukali and Wout van Tongeren

Composer Bushra El-Turk, director Kenza Koutchoukali and dramaturg and librettist Wout van Tongeren jointly developed the concept for Oum – A Son’s Quest for His Mother. During the second week of rehearsals, the makers reflect on their new creation.

Oum – A Son’s Quest for His Mother was inspired by the music of Oum Kalthoum. What role did her music play in your lives before you started on this project?

Kenza Koutchoukali: “My father was born and raised in Algeria. In the Middle East and North Africa, people say ‘you’re either for Oum Kalthoum or for Fairouz’. My father was a big fan of Fairouz but he also had a documentary DVD on Oum Kalthoum, which I now have at home.”

“My father had a complicated relationship with the country of his birth. Algeria was a French colony, so he went through the French school system, including studying in Paris. But despite the educational opportunities that the French occupation offered him, it was still a violent and oppressive regime. That must have been conflicting for him, and I think that is reflected in how Arab culture was a very prominent aspect of my father’s life at times and more a background element at other times.”

“My first conscious encounter with the music of Oum Kalthoum was when I listened to it at the invitation of Mohamed Aadroun, artistic director of the Amsterdams Andalusisch Orkest. It was remarkable how I immediately felt at home with the music, and especially the rhythms. I must have already heard the music more often than I realised.”

Bushra El-Turk: “For me, the music of Oum Kalthoum represents my parents’ lives before the outbreak of the civil war. My parents were born in Lebanon. For my father, who is somewhat older, the 1950s and 1960s — the period following independence from France — were a real golden age, and Oum Kalthoum was one of the great voices of that era. The civil war started in 1975. A couple of years later, my parents got married and fled to Britain, where I was born. When we visited Lebanon again after the war ended, my parents’ house was damaged but still standing. All the furniture was still there: an interior that must have been old-fashioned even before the war. I could imagine myself transported back to that golden age. There were also loads of records of Oum Kalthoum. When I hear her music now, I can smell that house again.”

Wout van Tongeren: “My connection with Oum Kalthoum is as an outsider. While talking to our partners in the Amsterdams Andalusisch Orkest and Meervaart, I discovered how much of a presence her music is here in the Netherlands too, although most people without roots in North Africa or the Middle East are probably unaware of this. I must have heard her music before in a taxi, or picked up snatches coming from a neighbour’s living room on a summer’s day. Even so, this project still feels like a first encounter because it’s only now that I have started listening to the music seriously. For the purposes of this project, I’ve made an effort to get to know a musical culture that is quite unlike the musical references I’m familiar with. I realise that many people with migrant backgrounds are constantly making this kind of effort, building bridges between the culture they grew up with at home and that of wider society where they are expected to be familiar with very different cultural codes.”

Kenza, you were the first maker to become involved in the project. How did that happen?

Kenza Koutchoukali: “At Dutch National Opera, I previously directed How Anansi freed the stories of the world, which was inspired by stories from West African and Caribbean culture. When I was working on that production, it occurred to me that I’d never created anything that drew on my own bicultural roots. I got talking to Mohamed Aadroun about that. Coincidentally, discussions were ongoing at around that time between ‘his’ Amsterdams Andalusisch Orkest, Dutch National Opera and Meervaart about a new collaborative project. They’d already decided the project should be one inspired by Oum Kalthoum. Then they asked me to shape the production artistically.”

How did you arrive at the concept for this production?

Kenza Koutchoukali: “I knew from the start that it shouldn’t be a biographical opera. How could you possibly present such an iconic singer in a music theatre performance? I preferred to do something with what Oum Kalthoum means to different generations in our society today.”

“I think it’s very important to know your cultural background so you can then embed it as you wish in the life you want to lead. But that means the society you live in has to accept that culture’s right to exist, and unfortunately that can’t be taken for granted these days. That gave me the idea of a story about someone struggling with their cultural background and therefore with themselves. Then Wout suggested we should look at the work of the Lebanese author Wajdi Mouawad.”

Wout van Tongeren: “I remember how that went. In one of our discussions, we thought of a basic story in which someone inherits a collection of music cassettes from their parents, intending to throw them away, but then starts listening to them. That brings the person into a dialogue with their parents’ culture. Which made me think of Wajdi Mouawad. His work deals with topics such as migration and the relationship between parents and their children. We were planning to approach him for the libretto, but then Kenza found his novel Visage retrouvé, a wonderful story that addresses precisely those themes we wanted to explore.”

Kenza Koutchoukali: “I’d also wanted to work with composer Bushra El-Turk for some time. I’d got to know her work through various contacts and when I came across this story, I knew at once she would be the ideal person to compose music for it. Bushra is a composer who seems to incorporate her identity naturally into what she writes, which is something I really admire. Some artists choose to deliberately hide that side of themselves, but not Bushra.”

Bushra El-Turk: “When Kenza approached me, I felt immediately that it would be good working with her. We clicked, partly because of our shared interests but also because of common aspects in our personal histories as children of diasporic parents. When Kenza told me about Wajdi Mouawad’s book, I felt we could turn it into something very powerful.”

“In the past few years, I’ve been wrestling with the question of how to embed my Arab roots in my music. When people see you as an Arab composer, they expect you to incorporate that into your work in a recognisable form. At times I have gone along with that, but it’s also something I’ve resisted at other times. I think it is important that people look beyond my roots; I’m more than just that.”

What do you take from Oum Kalthoum’s music?

Bushra El-Turk: “Oum Kalthoum’s music touches me at a very personal level. It’s not easy to work with material that you have so much respect for. There is a lot I want to leave intact, but during the process I’ve also discovered how much room there is in her music. It is very open and receptive to reinterpretation. That let me create a kind of kaleidoscopic work. Sometimes Oum Kalthoum takes pride of place in a very recognisable way, but there are also moments when I use elements from her music that the audience will barely notice. It’s as if you’re abstracting the pure essence from it.”

“Her music is also full of improvisation: no two concerts of hers were the same. I try to include that in the composition. Together with the musicians, I’m working on varying degrees of improvisation, from ornamentation around a prescribed melody to almost completely free improvisation.”

Oum Kalthoum’s song Al-Atlal has a prominent place in the production. Why did you chose that particular number?

Bushra El-Turk: “Al-Atlal is unbelievably complex. It also has a fragmented structure that makes it well-suited to our project. At the same time, the song is hugely emotional and communicative, which works very well in music theatre. When we delved into the text of Al-Atlal, we realised the number would be a good fit in that regard too: there are so many sentences in the song that give an extra dimension to the events in the opera. The song is really an opera in its own right, with its own narrative that interacts with the music theatre production that it is part of.”

Kenza Koutchoukali

“A canvas that everyone can project their own story on”

Kenza Koutchoukali: “The conceptual link has to do with the inner world of Wahab, the main character. He wants to be reconciled with his mother, from whom he has become alienated, which is really also a longing for reconciliation with himself. To achieve that, he needs to face up to a major trauma that he would obviously prefer to avoid. That translates into his relationship with the music. Only once Wahab has become reconciled with his mother can he accept the music of Oum Kalthoum in its entirety, and at that point in the performance Al-Atlal breaks out in its ‘pure’ form.”

“In the final analysis, the meaning of the song is quite bitter. The title refers to ruins and the number is about loss. That ties in with what Oum Kalthoum represents for a lot of people, namely the connection with the country of your forebears, the place where you will never feel completely at home again.”

Wasn’t dealing with this material nerve-racking or overwhelming at times?

Bushra El-Turk: “Of course it’s daunting to compose a work that enters into a dialogue with the music of such a great artist. But that applies to other projects as well. If you compose a string quartet, you always have to deal with the legacy of Mozart, Schubert and so on. It can be intimidating, but you need to do it. This project has also helped me better understand my parents’ world. I listened endlessly to old, crackling recordings of music from when they were young. This project is like a jigsaw puzzle for me where we try to fit all the pieces together.”

Kenza Koutchoukali: “It’s true this project feels like a puzzle, both artistically and personally. I was very keen to tackle these themes but I also wondered what right I had to work with this material. I only know Algeria as my father’s country. But even though I was born and raised here in the Netherlands, something about that place has always attracted me. How do you deal with that as a person? That’s basically what this opera is about. As a cultural phenomenon, Oum Kalthoum has become a canvas on which everyone can project their own story. Her work lends itself to this — Oum Kalthoum is incredibly generous in that respect.”

Dutch text: Maxim Paulissen

De nalatenschap van Oum Kalthoum

De naam Oum Kalthoum is bij velen bekend, maar wat maakt haar werk zo bijzonder? Musicoloog Lillie Gordon schetst een beeld van de nalatenschap van deze iconische artiest, en gaat in op de betekenis die haar muziek heeft voor talloze mensen in de Arabische wereld en ver daarbuiten.

For the translation of this article, read the original text here: EastEast

De nalatenschap van Oum Kalthoum

For the translation of this article, read the original text here: EastEast

De naam Oum Kalthoum is bij velen bekend, maar wat maakt haar werk zo bijzonder? Musicoloog Lillie Gordon schetst een beeld van de nalatenschap van deze iconische artiest, en gaat in op de betekenis die haar muziek heeft voor talloze mensen in de Arabische wereld en ver daarbuiten.

‘Al-Atlal’ is in de eerste plaats een melancholisch liefdeslied, zoals zoveel klassieke Egyptische liederen. Als individu leef je mee met de hoofdpersoon, die tussen ‘de ruïnes’ van een voorbije liefde staat. Je luistert vol verwondering en zingt misschien mee wanneer de zangeres je met extreme gevoeligheid en behendigheid meevoert van een verlangen dat “je ribben verbrandt” naar gelukkige herinneringen aan een romantische wandeling over “maanverlichte paden”. En toch, in het lied wordt duidelijk dat dit universele liefdesverhaal over meer gaat dan romantiek. De minnaar smeekt: “Geef me mijn vrijheid, ontketen mijn handen”. Meer dan vijftig jaar later gebruikt men deze zin nog steeds om onvrede met onrechtvaardige regeringen te uiten. (…)

Artiesten als Oum Kalthoum zijn zeldzaam. Haar muziek is een van de grootste artistieke prestaties in de Egyptische (en Arabische) muziekgeschiedenis, maar je hoort haar liederen evengoed geneuried worden in de rij bij de supermarkt of snoeihard door de speakers schallen tijdens een bruiloft. Gedurende haar vijftigjarige carrière en in de decennia daarna is ze de meest herkenbare stem van Egypte en misschien wel van het hele Arabische taalgebied geworden. Hoewel haar verhaal en muziek uitzonderlijk zijn, voelen ze aan als het verhaal van iedereen en vertellen ze een collectieve geschiedenis.

Een eigentijdse esthetiek

Gedurende haar hele carrière zette Oum Kalthoum een unieke mix in van esthetiek en beeldtaal die vakkundig aansloot bij de veranderende tijdgeest. Ze werd geboren in een plattelandsdorp in de agrarische regio van de Nijldelta rond het begin van de 20ste eeuw (ca. 1898-1904). Haar vader, Shaykh Ibrahim, leidde de plaatselijke moskee en zong in de omgeving op religieuze feestdagen en familiegelegenheden. Als kind moest Oum Kalthoum op de plaatselijke school de Koran uit het hoofd leren en voordragen, vaardigheden waar critici later haar verfijnde dictie aan toeschreven. Zelfs als volwassene, nadat Oum Kalthoum een meer kosmopolitische esthetiek had aangenomen, zou haar landelijke, volkse en religieuze opvoeding fans en politici aanspreken die op zoek waren naar een eenvoudige, rechtschapen en uniek-Egyptische culturele vertegenwoordiger.

Na aanvankelijke reserves om zijn dochter in het openbaar te laten optreden uit bezorgdheid over haar reputatie als vrouw, besloot Shaykh Ibrahim uiteindelijk Oum Kalthoum op te nemen in de zanggroep van het gezin. Naar verluidt kleedde haar vader haar aanvankelijk als jongen, meer om zijn eigen ongemak met haar deelname aan de groep te verzachten dan om het publiek voor de gek te houden. Met de groep trad Oum Kalthoum overal in de regio op met religieus repertoire, soms in de huizen van plaatselijke notabelen met verreikende connecties. Haar reputatie als zangeres groeide naarmate de familie steeds verder reisde voor optredens, vaak per trein, waardoor ze haar honorarium kon verhogen en haar familie kon onderhouden.

Aangemoedigd door verschillende mecenassen met goede connecties, verhuisde de familie van Oum Kalthoum begin jaren ’20 naar Caïro. In een golf van stedelijke migratie verhuisden destijds duizenden families van het platteland naar Caïro, het industriële, commerciële en mediacentrum van Egypte. Daar begon Oum Kalthoum voor het eerst op te treden met een klein instrumentaal ensemble (takht), wat haar een onmiskenbaar stedelijk geluid bezorgde. Haar takht bestond uit een aantal van de beste instrumentalisten van Egypte, waaronder violist Sami al-Shawwa en udspeler en componist Muhammad al-Qasabji. Ze organiseerden openbare concerten (een nieuw fenomeen), met een (soms luidruchtig) publiek dat bestond uit Egyptenaren, Europeanen en leden van de Ottomaanse elite. In navolging van de mode van die tijd begon ze ook seculiere liederen te zingen, waarvan sommige botsten met haar imago van plattelandsmeisje. Uiteindelijk liet Oum Kalthoum dat imago achter zich en omarmde ze nieuwe technologieën en modes, terwijl ze een mate van bescheidenheid behield waar andere vrouwelijke artiesten in die tijd minder waarde aan hechtten.

Oum Kalthoum maakte haar eerste opnames aan het begin van de jaren ’20, maar volgens biograaf en etnomusicoloog Virginia Danielson zijn haar opnames uit 1927 de echte start van haar carrière. Liederen als ‘In Kunt ‘Asamih’ (compositie Muhammad al-Qasabji, tekst Ahmed Rami) voldeden aan de tijdsgeest door klassieke kunstzinnigheid, moderne esthetiek en romantische poëzie te combineren. Sinds haar komst naar Caïro kreeg Oum Kalthoum les van de beroemde docent al-Shaykh Abu-l-’Ila Muhammad. Hoewel ze al een volleerd zangeres was, vergrootte deze leraar haar kennis van het Arabische klassieke melodie- en poëzierepertoire, van de techniek van stembeheersing en bovenal van de wijze waarop ze de betekenis van de tekst kon verwerken in haar vocale uitvoering. Tegelijkertijd combineerde Muhammad al-Qasabji in zijn composities tertsen en grote melodische sprongen, die het publiek ‘Europees’ in de oren klonken, met bewegingen die typisch waren voor het Arabische tonale systeem van maqams (toonladders met de bijbehorende overlevering van veelgebruikte frasen en accenten, red.). Ten slotte versmolt Ahmed Rami’s poëzie een zinsbouw die verwant is aan romantische poëzie met beeldspraak die gebruikelijk is in Arabische liederen. Oum Kalthoum combineerde deze elementen met haar vocale expressie, waaronder het zorgvuldige gebruik van schorheid en een breed vibrato, om een mix te creëren die werd ervaren als modern, klassiek en gegrond. Hoewel haar vroege repertoire niet haar meest bekende is gebleven, omvatte het wel het veelzijdige moment waarop het ontstond.

Herhalen en opnieuw vormgeven

Oum Kalthoums bekendheid groeide niet alleen door opnames, maar ook doordat zij andere nieuwe media als radio en film omarmde. Vanaf 1934 begon de Egyptische (nationale) radio haar liederen en uiteindelijk ook haar live optredens op de eerste donderdag van elke maand uit te zenden. Omdat de donderdagavond het begin van het weekend markeerde in overwegend islamitische landen zoals Egypte, kregen deze uitzendingen het karakter van nationale evenementen. Inwoners van Caïro herinneren zich dat de doorgaans luidruchtige en drukke straten van de stad op die donderdagavonden ongewoon stil werden, omdat de meeste mensen zich verzamelden rond hun radio’s thuis of in openbare ruimten, waaronder de duizenden cafés van Caïro. Door deze uitzendingen werd Oum Kalthoum een nationaal ankerpunt, een vast onderdeel van ieders maandelijkse routine, ritme en rituelen. (…)

Oum Kalthoum omarmde ook de film en speelde in de jaren ’30 en ’40 in zes speelfilms. Veel mensen beschouwen deze periode als het hoogtepunt van de Egyptische cinema – en met Caïro als het mediacentrum van de Arabische wereld in die tijd, waren Egyptische films ver buiten de landsgrenzen te zien. Haar films, net als haar liederen, boden een combinatie van moderne en traditionele esthetiek. Waar de helft van haar films historische drama’s waren, legde de andere helft de klassenverschillen en sociaal-culturele spanningen van die tijd bloot. In de film Fatma (1947) speelt Oum Kalthoum een verpleegster die verleid wordt door de broer van een rijke patiënt. Hij trouwt met haar, maar laat haar dan weer vallen, uit afkeer van de arbeiderswijk waar zij onder de inwoners een graag geziene figuur is. Uiteindelijk helpen haar buren haar om de boosdoener aan te klagen. De film plaatst de deugdzaamheid en loyaliteit van de arbeidersklasse in contrast met de losbandigheid en het corrupte gedrag van de rijken, een voorbode van de Egyptische revolutie die slechts vijf jaar later zou plaatsvinden.

In haar films zong Oum Kalthoum voornamelijk korte, gevarieerde liedjes. Deze stonden in schril contrast met haar optredens, waarin ze bekend stond om het verlengen van liederen door middel van herhalingen en variaties. Tegen de jaren ’40 specialiseerde ze zich in een lang liedformat dat vaak ‘ughniyya’ wordt genoemd, een meerdelige compositie met contrasterende instrumentale en vocale secties, waarbij het enige herhaalde materiaal van de oorspronkelijke composities in de laatste paar regels van de vocale delen zit. Het eerder genoemde ‘Al-Atlal’ is een goed voorbeeld van dit type lied. Oum Kalthoum gebruikte haar korte filmliedjes vaak als basis voor deze langere versies, waarbij ze een origineel van vijf minuten soms wel een uur liet duren. (…)

Veranderend politiek landschap

Oum Kalthoums positie als symbool van het nieuwe Egypte is ook verbonden met de wijze waarop ze zich engageerde met het veranderende politieke landschap. Ze kende koning Farouk I en werd in haar vroege jaren door hem onderscheiden. Ondanks aanvankelijke reserves, besloot Gamal Abdel Nasser na zijn revolutie van 1952 om de liefde van het volk voor de ster te benutten en promootte hij haar op grote schaal op de staatsradio. Veel Egyptenaren zagen parallellen tussen de twee figuren, die beiden voortkwamen uit de landelijke arbeidersklasse en uitgroeiden tot symbolen van het moderne Egypte.

Volgens musicoloog Laura Lohman begon Oum Kalthoum zich vanaf de jaren ’50 doelbewust patriottistisch te profileren. Met ‘Concerten voor Egypte’ trad ze op door het hele Midden- Oosten en Europa om geld in te zamelen voor de regering na de nederlaag van Egypte in de zesdaagse oorlog van 1967. Nu zij een internationale superster was, promootte ze de pan-Arabische agenda van Nasser en ontplooide ze ook een aantal humanitaire initiatieven. Naast de overvloedige creativiteit in haar optredens zelf, nam ze ook niet-muzikale stappen om haar publieke imago vorm te geven.

Tarab - Extase

Oum Kalthoum onderscheidt zich misschien wel het meest door haar beheersing van wat al van oudsher het esthetische doel van Arabische kunstmuziek was: tarab. Tarab is een moeilijk te vertalen woord, dat niet volledig kan worden omschreven als ‘betovering’ of ‘extase’. Het beschrijft het gevoel volledig op te gaan in de emotionele inhoud van een kunstwerk, meestal muziek. Zangers worden vaak ‘mutrib’/’mutriba’ genoemd, een woord met dezelfde etymologische oorsprong. (…) Oum Kalthoum bracht al haar invloeden, esthetische keuzes en vaardigheden succesvol samen om toe te werken naar gevoelens van tarab. Het bijwonen van haar optredens en het luisteren naar haar opnames bracht haar publiek diep in vervoering, waardoor er ruimte ontstond om melancholie en emotioneel conflict te beleven. (…)

Nalatenschap

Meer dan veertig jaar na haar dood in 1975 blijft Oum Kalthoum een centrale figuur in Egypte, de Arabische wereld en daarbuiten. Sommige Egyptische radiostations zenden nog steeds op gezette tijden een van haar lange liederen uit. Deze uitzendingen schallen door wijken vanuit de alomtegenwoordige cafés in Caïro, waar veel mensen hun avonden doorbrengen. Haar muziek wordt vertolkt tijdens zangwedstrijden op televisie, door religieuze muziekgroepen en door topzangeressen uit de Arabische wereld, waaronder Nancy Ajram. Er zijns zelfs hologramconcerten van de artiest georganiseerd. Als iemand in Egypte je vraagt: “Wat zegt ‘de dame’?”, word je uitgedaagd om een citaat uit een Oum Kalthoum-nummer te noemen dat bij je huidige situatie past.

De muziek van Oum Kalthoum is vele dingen. Ze is ‘een leerschool’, bestudeerd binnen de meest gerenommeerde Arabische muziekacademies. Haar muziek is een feest, want haar liederen weerklinken tussen hedendaagse populaire liederen op bruiloften binnen alle sociale klassen. Soms draagt haar muziek bij aan een volksrevolutie. Tot slot zijn haar liederen kunstwerken: innovatief, prachtig, alom bekend en innig geliefd.

Tekst: Dr. Lillie S. Gordon, Northern Arizona University

Vertaling en inkorting: Maxim Paulissen

For the translation of this article, read the original text here: EastEast

On the work of Wajdi Mouawad

Wajdi Mouawad’s oeuvre seems to be a constant reckoning with his personal history. And yet his work transcends the particular; Mouawad transforms his own experiences into a powerful and compelling literary form.

On the work of Wajdi Mouawad

Wajdi Mouawad’s oeuvre seems to be a constant reckoning with his personal history. And yet his work transcends the particular; Mouawad transforms his own experiences into a powerful and compelling literary form.

Wajdi Mouawad is one of the most prominent playwrights of his generation. His plays have been performed in many countries. In the Netherlands he is best known for Tous des oiseaux (Birds of a Kind), performed as Vogels in 2023 by ITA, and Incendies (Scorched), performed as Branden by RO Theater in 2010 and Toneelgroep Oostpool and Toneelschuur Producties in 2024/2025.

Mouawad spent the first ten years of his life in Lebanon. In 1978, during the Lebanese civil war, Mouawad and the rest of his family fled to France while his father stayed behind to work. Five years later, the family moved to Quebec in Canada. Mouawad found it difficult to settle there — he played truant a lot, preferring to spend his time in cinemas — until he auditioned for a theatre course and was accepted. He subsequently developed into an actor, director and writer. Mouawad has led various theatre companies and became director of La Colline – théâtre national in Paris in 2016.

Mouawad’s writing has a distinctive personal style: full of imagery, rich in emotion and with an emphasis on monologues. His characters appear to use language in an attempt to get a grip on their own existence and the world around them. That makes the key role he assigns to silence — the refusal to speak — all the more striking in his stories replete with such eloquent characters. However, a character’s silence does not prevent them from communicating with the audience. In Oum – A Son’s Quest for His Mother, the main character Wahab is constantly talking, but his monologues show that in fact he tells his family very little.

Certain elements turn up frequently in Mouawad’s plays and novels, such as twins, ghostly appearances and animal figures. There are also recurring themes that draw on his personal history: migration, broken families and coping with loss and violence. Many of Mouawad’s texts refer implicitly or explicitly to the civil war, which he experienced as a child. That is also the case for the texts on which the music theatre production Oum – A Son’s Quest for His Mother is based.

Wahab’s story

The production’s libretto is based on Mouawad’s play Un obus dan le coeur (A bomb in the heart) which in turn is an adaptation of his debut novel Visage retrouvé (Face rediscovered). The novel is from the perspective of Abdelwahab, whom everyone calls Wahab.

In the first chapter, ‘Le temps’ (Time), Wahab describes a carefree childhood that ends abruptly when he witnesses an appalling massacre. His family decides to flee the war that has now broken out. “Tomorrow we will be taking the plane. A distant, rainy country awaits me. I wish I never had to say ‘I’ again, that I never had to get involved in anything again. I wish someone would say ‘he’ for me. Relieve me of myself.”

Indeed, the next two chapters are written in the third person. They cover a period of several days in Wahab’s new homeland, a few years after fleeing the country of his birth. In ‘La peur’ (Fear), he is given a front-door key on his fourteenth birthday as confirmation of his growing independence. However, the day takes a horrific turn when Wahab returns home from school to discover his mother has acquired a completely new face. Distraught, he runs away from home.

In the chapter ‘La beauté’ (Beauty), he describes his journey through a winter landscape. Wahab experiences the raw, overwhelming power of nature and has a mysterious encounter with a silent girl. When the police bring him back home, he clings onto this experience of a beauty he has rediscovered after it was swept away by the violence of war during his childhood.

In the final chapter, ‘La colère’ (Anger), Wahab is nineteen and starting out as a painter. The return to the first person form suggests he has regained some control over his life. And yet the transformation of his mother remains a mystery and he still carries the burden of his childhood trauma. The play and the music theatre production largely follow the story in this fourth chapter. Wahab is on his way to the hospital where his mother is on her deathbed. He reflects on his life in a constant flow of words, saturated in anger. Finally, at his dying mother’s bedside, Wahab undergoes a cathartic experience and solves the mystery of the transformation of her appearance. This lets him reconcile himself with his past.

The legacy of anger

Anger, the title of the final chapter, is a recurring theme in Mouawad’s oeuvre. Talking about this in an interview in 2019, he said,

“That anger has nothing to do with being reasonable. It seizes me, it holds me in its grasp. That anger is not mine: I inherited it from an entire culture, from an entire generation that experienced the civil war and never had an opportunity to give voice to their anger. I am the heir inheriting that anger and I have chosen to dedicate part of my life to expressing it. (…) I feel like I am the storehouse of a primeval anger that precedes and transcends that of my generation. Writing is a place to remember that anger.” (Études, March 2019)

Mouawad’s writing seems in many respects to be a response to the violence he saw as a child and the hatred that drove that violence. In a recent interview in Le Monde, he said that his exile has given him something important, namely:

“The desire and curiosity to seek out those I had learned to hate – namely the stranger, the Other. Like many Lebanese, I had been taught to believe that those who were not like me were a threat, that we were the victims and they the villains. I felt a longing for rapprochement with the Sunnis, the Shiites, the Palestinians, the Israelis, the Jews — all those people I had learned to hate. Not only did I have a wish to meet them, I also turned them into the protagonists of my works. That urge for reconciliation, for harmony has really come through being in exile.” (Le Monde, 3 November 2024)

An assault on the spectator

Mouawad’s acknowledgement of the feelings of anger and hatred that he harbours, and his efforts to get to know the Other despite those feelings, make his texts hugely relevant. This is precisely what gives his work an impact that transcends the particular, despite being rooted in highly personal experiences. It expresses feelings that, if ignored, can easily lead to aggression. This is literature that supplants violence, not by tempering the emotions that drive that violence but by giving them a voice and enabling them to be expressed through art. His texts transform the real violence lurking in society into an aesthetic ‘assault’ on the spectator:

“I wanted to commit symbolic assaults: I wanted bombs to fall in people’s minds. The bomb was the story and the emotion it conveyed. I wanted spectators to leave at the end of the performance feeling shocked, shattered.” (Études, March 2019)

This ‘assault poetry’ is neither cynical nor nihilist. Mouawad often gives his plays a hopeful ending. Troubled characters find a sense of peace; traumas that children inherited from their parents appear to be healed. “Ultimately, it depends on how you decide to end your story. I don’t want to make the end pitiless, because I’m not a pessimist.” (Sens-Dessous, January 2007). Mouawad’s work, which seeks out ‘strangers’ and acknowledges humanity’s dark side, is more urgent than ever today, in a world that is increasingly polarised and in which even the hitherto safe haven of Western Europe is in danger of becoming embroiled in violent conflicts.

Dutch text: Wout van Tongeren