Turandot online programme

Performance information

Voorstellingsinformatie

Performance information

Duration

2 hours, no interval

The performance is sung in Italian.

Dutch subtitles based on the translation by Ivette Brusselmans.

English subtitles courtesy of Andrew Kingsmill.

Makers

Libretto

Giuseppe Adami & Renato Simoni

Conductor

Lorenzo Viotti

Director

Barrie Kosky

Set design

Michael Levine

Costume design

Victoria Behr

Lighting design

Alessandro Carletti

Choreography

Otto Pichler

Cast

La principessa Turandot

Tamara Wilson

L’imperatore Altoum

Marcel Reijans

Timur

Liang Li (2, 4, 6, 9, 17, 21, 23, 28 & 30 dec)

Alexei Kulagin (12, 14 & 25 dec)

Il principe ignoto (Calaf)

Najmiddin Mavlyanov (2, 6, 9, 17, 21 & 28 dec)

Martin Muehle (4, 12, 14, 23, 25 & 30 dec)

Liù

Kristina Mkhitaryan (2, 6, 9, 17, 21 & 28 dec)

Juliana Grigoryan (4, 12, 14, 23, 25 & 30 dec)

Ping / Un mandarino

Germán Olvera

Pang

Ya-Chung Huang

Pong

Lucas van Lierop

Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Chorus master

Edward Ananian-Cooper

Nieuw Amsterdams Kinderkoor (part of Nieuw Vocaal Amsterdam)

Children’s chorus master

Sanne Nieuwenhuijsen

Productieteam

Assistant conductor

Boudewijn Jansen

Junior assistant conductor

Giuseppe Mengoli

Assistant director

Astrid van den Akker

Junior assistant director

Noah van Renswoude

Assistant choreographer

Klevis Elmazaj

Assistant director during performances

Astrid van den Akker

Noah van Renswoude

Directing intern

Inge-Vera Lipsius

Rehearsal pianists

Peter Lockwood

Ernst Munneke

Language coach

Marco Canepa

Language coach chorus

Valentina di Taranto

Assistant chorus master

Ad Broeksteeg

Stage managers

Marie-José Litjens

Roland Lammers van Toorenburg

Niek Stroomer

Sanne Tukker

Artistic affairs and planning

Emma Becker

Orchestra inspector

Frouke Terpstra

Assistant set design

Yannick Verweij

Costume supervisor

Jojanneke Gremmen

Master carpenter

Peter Brem

Lighting manager

Peter van der Sluis

Props manager

Peter Paul Oort

Remco Holleboom

Special Effects

Ruud Sloos

Koen Roggekamp

First dresser

Sandra Bloos

First make-up artist

Salome Bigler

Sound technician

David te Marvelde

Florian Jankowski

Dramaturgy

Laura Roling

Surtitle director

Eveline Karssen

Surtitle operator

Jan Hemmer

Set supervisor

Sieger Kotterer

Production management

Joshua de Kuyper

Chorus of Dutch National Opera

Sopranos

Esther Adelaar

Patricia Atallah

Diana Axentii Lisette Bolle

Bernadette Bouthoorn

Else-Linde Buitenhuis

Jeanneke van Buul (solo)

Caroline Cartens

Zane Danga

Anna Emelianova

Melanie Greve

Deasy Hartanto

Frédérique Klooster

Oleksandra Lenyshyn

Simone van Lieshout

Tomoko Makuuchi (solo)

Vida Maticic Malnarsic

Elizabeth Poz

Janine Scheepers

Jannelieke Schmidt

Kiyoko Tachikawa

Claudia Wijers

Altos

Irmgard von Asmuth

Maaike Bakker

Elsa Barthas

Ellen van Beek

Anneleen Bijnen

Rut Codina Palacio

Johanna Dur

Valérie Friesen

Yvonne Kok

Fang Fang Kong

Carlijn Kooijmans

Maria Kowan

Myra Kroese

Liesbeth van der Loop

Itzel Medecigo

Maaike Molenaar

Emma Nelson

Sophia Patsi

Carla Schaap

Irina Scheelbeek-Bedicova

Klarijn Verkaart

Ruth Willemse

Tenors

Thomas de Bruijn

Wim Jan van Deuveren

Frank Engel

Milan Faas

Ruud Fiselier

Cato Fordham

Livio Gabbrielli

John van Halteren

Robert Kops

Roy Mahendratha

Tigran Matinyan

Frank Nieuwenkamp

Sullivan Noulard

Martin van Os

Richard Prada

Mitch Raemaekers

Mirco Schmidt

Raymond Sepe

François Soons (solo)

Julien Traniello

Jeroen de Vaal

Bert Visser

Rudi de Vries

Basses

Ronald Aijtink

Bora Balci

Nicolas Clemens

Emmanuel Franco

Jeroen van Glabbeek

Jan Willem van der Hagen

Julian Hartman

Agris Hartmanis

Hans Pieter Herman

Sander Heutinck

Tom Jansen

Michal Karski

Richard Meijer

Matthijs Mesdag

Maksym Nazarenko

Wojtek Okraska

Christiaan Peters

Hans Pootjes

Matthijs Schelvis

Jaap Sletterink

Ian Spencer

René Steur

Rob Wanders

Nieuw Amsterdams Kinderkoor

Part of Nieuw Vocaal Amsterdam

Alessia Letz

Alice Chatron-Bennett

Anaís Matias Khmelinskaia

Barbara Klee

Bram de Bree

Calla Kemper

Dimitri Bos

Eden Vos

Eva Thijs

Helena Huipe

Helena Jeremiasse

Iris Thijs

Jonathan Lever

Kate van den Broek

Lavinia Weststeijn

Lena Koedam

Lidewij Nieuwenhuizen

Lieneke Homan

Linde Bijvoet

Liva Ririassa

Lois Nollet

Luzia Keuzenkamp

Mara Jacobs

Max Munnecom

Natasja Provily

Nora van den Nieuwenhof

Rhinja Simons

Sanne Mostert

Sarah Lever

Sophia Habashi

Zeynep Ayar

Dancers

Rachele Chinellato

Lili Kok

Sho Nakasatomi

Renzo Popolizio

Valentin Quitman

Guillaume Rabain

Teresa Royo

Alicia Verdú Macián

Extras

Alaaedin Baker

Andrea James Child

Frans Dam

Bronwyn Henebury

Lidiane Morena

Federica Panariello

Rowin Prins

Evgenia Rubanova

Floor Scholten

Alexey Shkolnik

Anton van der Sluis

Sien Vanderostijne

Joy Verberk

Lotte Aimée de Weert

Liza Zhukova

Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra

First violin

Vadim Tsibulevsky

Saskia Viersen

Camille Joubert

Paul Reijn

Anuschka Franken

Henrik Svahnström

Marina Malkin

Mascha van Sloten

Derk Lottman

Stephanie van Duijn

Valentina Bernardone

Tessa Badenhoop

Marieke Kosters

Sandra Karres

Catharina Ungvari

Second violin

David Peralta Alegre

Marlene Dijkstra

Charlotte Basalo Vázquez

Jarmila Delaporte

Marieke Boot

Lilit Poghosyan Grigoryants

Eva de Vries

Karina Korevaar

Jeanine van Amsterdam

Anita Jongerman

Floortje Gerritsen

João Filipe Farinha Fernandes

Wiesje Nuiver

Viola

Dagmar Korbar

Laura van der Stoep

Odile Torenbeek

Stephanie Steiner

Suzanne Dijkstra

Ernst Grapperhaus

Michiel Holtrop

Avi Malkin

Karen de Wit

Anna Smith

Cello

Ilia Laporev

Douw Fonda

Anjali Tanna

Rik Otto

Nitzan Laster

Carin Nelson

Atie Aarts

Emma Kroon

Sebastian Koloski

Double bass

Luis Cabrera Martin

Mario Torres Valdivieso

Gabriel Abad Varela

Julien Beijer

Larissa Klipp

Antonio Muedra Ventura

Dobril Popdimitrov

Flute

Leon Berendse

Liset Pennings

Eva Vennekens

Oboe

Jeroen Soors

Maria Teresa

Martinez Risueño

Vincent van Wijk

Clarinet

Leon Bosch

Maria du Toit

Herman Draaisma

On-stage saxophone

Juan Manuel Dominguez

Carlos Gimenez Martinez

Oboe

Margreet Bongers

Dymphna van Dooremaal

Jaap de Vries

Horn

Fokke van Heel

Fred Molenaar

Miek Laforce

Stef Jongbloed

Trumpet

Gertjan Loot

Jeroen Botma

Marc Speetjens

On-stage trumpet

Andreu Vidal Siquier

Sven Berkelmans

Tiago Abranchez Baeza

Anneke Romeijn

Abigail Rowland

Rianne Schoemaker

Trombone

Harrie de Lange

Wim Hendriks

Wouter Iseger

Marijn Migchielsen

On-stage trombone

Wilco Kamminga

Joao Mendes Canelas

Reinaldo Donoso Pizarro

Timpani

Theun van Nieuwburg

Percussion

Matthijs van Driel

Diego Jaen Garcia

Lennard Nijs

Andrea Tiddi

Bence Csepeli

On-stage percussion

Wilbert Grootenboer

Harp

Sandrine Chatron

Jaike Bakker

Celesta

Celia Garcia Garcia

The story

Follow the link below to read the story of Turandot.

The story

Princess Turandot challenges any prince, who dares to vie for her hand in marriage, to solve three impossible riddles. A bloody execution awaits those who fail. Far from being deterred by the threat of death, potential suitors continue to announce themselves.

Prince Calaf too becomes enchanted by Turandot and will do anything to win her hand. Even his elderly father Timur and the loyal servant girl Liù, who is secretly in love with him, are unable to change his mind.

Calaf manages to answer the three riddles correctly. When Turandot refuses to accept his victory, Calaf offers Turandot a challenge of his own: If she can learn his name by dawn, he will forfeit his life.

The city’s inhabitants desperately try to find out the name of the mysterious prince. On Turandot’s instruction they capture Timur and Liù. Liù is tortured, but she remains silent, refusing to reveal Calaf’s name. She then grabs a dagger and kills herself.

Text & English translation: Laura Roling

‘Turandot was a true experiment for Puccini’

Director Barrie Kosky on Turandot, the second of three Puccini operas he is bringing to Dutch National Opera.

‘Turandot was a true experiment for Puccini’

Turandot is Puccini’s final, unfinished opera. In what sense does it differ from Tosca, which was composed some twenty years earlier in Puccini’s career?

The differences are massive. The music for both operas is very much recognisable as Puccini, but the style, the structure and the content of Turandot is completely different. Tosca belongs to the canon of works by Puccini that focuses on psychological storytelling and is an expression of an almost anti-Wagnerian approach to music theatre. With Turandot, towards the end of his life, Puccini made a complete U-turn and started to experiment with things he had never done before. He opted for a rather abstract fairy story, which he reworked to make even more abstract. He populates his stage with archetypes rather than the very real characters of his earlier works. So in many ways, Turandot was a true experiment for Puccini.

An experiment, however, that was left unfinished: Puccini died before finishing the opera. What does that mean?

We know that Puccini was struggling with the opera before he died. He had created a few problems for himself, the major one being that he had invented the character of the servant girl Liù and had made her the emotional centre point of the opera. Being an Italian composer at the turn of the century, he apparently couldn’t resist having a suffering young woman in his opera. Her suffering and suicide, however, is a direct consequence of Turandot’s actions, and turns all sympathy against the title role, creating an immense dramaturgical problem. We know that Puccini’s plan was to write a final love duet for Turandot and Calaf of Tristan und Isolde-esque proportions, which was to end very softly and quietly.

What happened after his death, however, is that Franco Alfano finished the opera and did the exact opposite, ending the opera with the full chorus and the singers just screaming their lungs out. For me, it has nothing to do with what Puccini envisioned.

When you worked on Tosca, you said that the score gives directors a clear roadmap, almost as though Puccini was directing the opera as he was writing it. Is that also the case with Turandot?

No, absolutely not, and I think it may have something to do with the massive chorus. Also, there is not a lot of drama in the piece. It’s very suspenseful nevertheless, but there are vast passages where people are just explaining things, rather than things actually happening. In this sense, it’s the polar opposite of Tosca. When talking to Lorenzo Viotti the other day, we discussed how we feel that Turandot was such a transition piece for Puccini. I think it’s the work after Turandot that would have been even more extraordinary, with a composer who’s comfortable with a new way of telling stories.

Puccini never went to China. He collected a few Chinese melodies, but in the end, Turandot presents a Western, clichéd and not entirely unproblematic version of China. There have even been heated discussions whether we should still stage Turandot today. What are your thoughts about this?

Yes, there is a problem with Turandot, but the answer to that problem is not to stop performing it. I don’t believe the answer to dealing with the ‘problem children’ like Turandot ever is to ban them from the stage entirely. I think that’s actually a very dangerous tendency. I don’t believe in destroying statues either. I do believe in contextualising them, in moving them to a different place or placing other statues beside them. Destroying things, destroying or denying history, is not the answer.

The exoticism of Turandot is not the only problem with the opera, by the way. If you look at the way the character of Turandot is presented, there’s also quite some misogyny at play. It is my job as a director to contextualise such issues and to find a way to present the opera in a different light and to make it work for contemporary audiences. That has been done a lot throughout the history of theatre. The way Shakespeare has been performed has also changed radically over the centuries. Why not opera?

So how did you deal with the orientalism of the opera in your interpretation?

Together with my team, I decided to leave all the exoticism in the orchestra pit and to go into an entirely different direction on stage. Turandot does not work as a realistic piece anyway. If you try to stage it with the idea that it tells a deep psychological story like Tosca or Manon Lescaut, then you’re doomed. The characters simply are not complex enough to support such an interpretation, and they were not intended to be. Rather, they are the archetypes that you would encounter in a fairy story or in a dream.

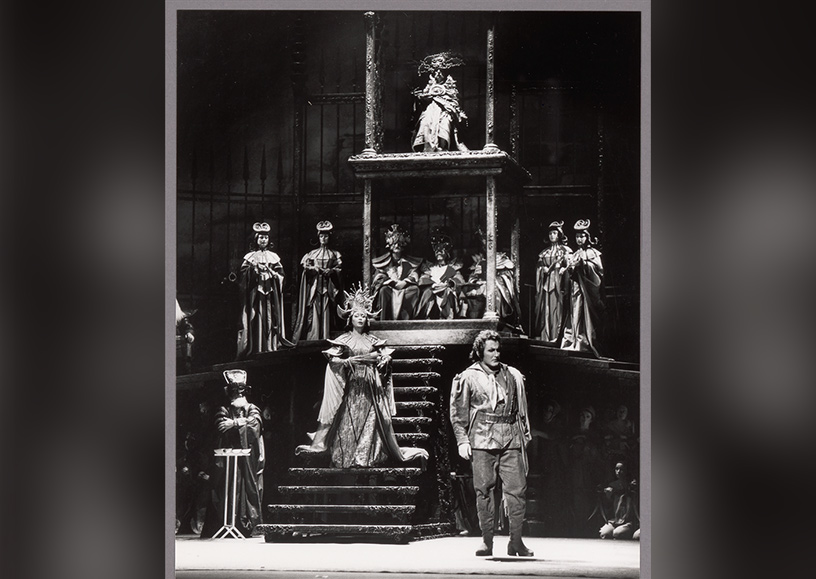

In your interpretation, the chorus takes centre stage. Why is that?

I think the chorus is the motor of the piece. They are highly mercurial: their moods and opinions change constantly. One moment, they are eagerly looking forward to the punishment of one of Turandot’s suitors, the next they are suddenly full of sympathy towards Calaf. They seem to adore and hate Turandot at the same time. It’s almost like they are traumatised or shellshocked. Their behaviour is irrational and dream-like. That’s what I found particularly fascinating and what gave me the idea to interpret the opera as a collective dream. There are also lots of references to dreaming, sleeping and sleeplessness in the opera’s libretto. Even the work’s most iconic aria is called ‘Nessun dorma’ (No one sleeps). That’s the type of dream-state we’re dealing with – an insomniac’s dream, incoherent, scary and restless.

In this dream, Turandot is an amalgamation on which all the collective’s desires and fears are projected. That’s why she has no physical presence in my production – she only exists as a voice.

Your interpretation leans much more towards the nightmarish than the dreamy. Why is that?

Just have a close look at the libretto. The text is full of images of torture and humiliation – there are even references to scraping the skin off people’s bodies. The chorus quite literally calls out for blood. One of the lead characters – the most sympathetic one at that – commits suicide. In essence, this is an extremely dystopian fairy story. Some stagings would have you believe otherwise, but in my opinion they’re not doing justice to the libretto.

As you said earlier, your production won’t have any of the Alfano endings, nor will we hear Luciano Berio’s music. How does the opera end? Will you simply drop the curtain after Liù’s death?

Lorenzo Viotti and I have talked about the ending a lot, and we came up with the idea for something new, some sort of epilogue in which the collective wakes up from its dream, as though Liù’s death has broken something. For this epilogue, we will be using elements of the Italian text, but there will be no music to accompany it. It will probably be a very quiet, hushed epilogue, but it’s still very much in the making – so we’ll see at the premiere!

Text: Laura Roling

Puccini’s impossible task

On the creation of Turandot and the missing finale.

Puccini’s impossible task

Giacomo Puccini set a new course with Turandot, but its creation was a lengthy and arduous process. The ending in particular posed a challenge for the composer and his librettists: how could they make Turandot’s transformation from a cruel and aloof woman into a submissive lover seem believable? When Puccini died, the opera was still unfinished. What solutions have been proposed since then to give Turandot a satisfying conclusion?

After the 1918 premiere of Il Trittico, a trio of stylistically divergent one-act operas, Puccini did not have an immediately obvious subject for his next opera. None of the ideas that were suggested enthused him, until the journalist and playwright Renato Simoni proposed the eighteenth-century Venetian dramatist Carlo Gozzi. His stylised, lively plays, rich in fantasy and known for their satire and absurdism, were deeply embedded in the Italian tradition of the commedia dell’arte and seemed ideally suited as a source for an opera. The choice fell on Gozzi’s masterpiece Turandot, based on a story – possibly of Persian or Chinese origin – about a man-hating princess who eventually discovers the transformative power of love.

The human aspect

Simoni set to work on adapting Turandot to an opera in partnership with Giuseppe Adami. The latter had introduced Simoni to Puccini and had already collaborated with the composer on La rondine and Il tabarro. When they presented their first rough drafts, Puccini found a lot that he admired and thought inspiring, but one essential element was lacking. The composer compared the confrontation between Calaf and Turandot to a duel between giants, but he felt that the human aspect was missing. Women whose lives revolve around love and passion had been at the centre of nearly all of Puccini’s operas, but he did not see such a woman in the title role of his new opera. He instructed Adami and Simoni to come up with a second female character who could serve as a dramatic counterweight to the hard-bitten princess. The librettists complied with his wishes and created Liù, the faithful servant who devoted her whole life to the prince’s elderly father. She fell hopelessly in love with Prince Calaf after he once smiled at her in the palace, a love that eventually drives her to sacrifice her own life. Puccini was thus able to sneak one of his sympathetic piccole donne into the opera.

After the initial drafts, the creation process faltered frequently. Simoni and Adami were both working on other projects and the impatient Puccini felt they were not delivering the verses he needed fast enough. Moreover, Puccini was regularly plagued by doubt and despair. This had been the case with his previous operas too, but it was particularly problematic with this opera. For example, he struggled with the scenes for the three masked courtiers Ping, Pang and Pong. They were drawn from the Italian commedia dell’arte, and the idea was that they should offer light relief in contrast to their elevated environment.

This required an experimental, grotesque music style that Puccini had not previously used in this way. The characters needed to be both humorous and severe, menacing even. Once again, Puccini sought something he could relate to in the drama: the human side of a cruel, inhuman and inflexible regime.

The problematic finale

It soon became clear to Puccini and his librettists that the main dramatic challenge would be how to end the opera. How could they give shape to Turandot’s transformation from ice princess into loving woman? It is telling that at least five versions of the text for the final duet had to be produced before Puccini was able to write “They [the lines of verse] are truly beautiful; they complete the duet properly and justify it”. One of the opera’s problems lies in its uneasy balance between a fairy-tale world with superhuman characters on the one hand, and the recognisable human emotions that Puccini needed for his creative process on the other. The composer succeeded admirably in differentiating the two main female roles: Turandot is vocally jagged and aloof, frighteningly haughty, whereas Liù is constant legato and glowing warmth.

But by creating this contrast between the two female roles, Puccini pushed himself into a corner. It would have been difficult to render Turandot’s sudden transformation any credibility anyway, but now this had become virtually impossible: when Liù commits suicide under torture, all the audience’s sympathy is directed towards Liù and away from Turandot. Even if it is Liù’s sacrificial death that causes Turandot to waver and sets off the process by which the princess finally thaws, it is difficult for audiences to forgive Turandot for the death of this particular victim in the final stage of the opera. The executions of Turandot’s suitors are forgivable – but Liù’s death is not. In Gozzi’s play, the irony and absurdism meant the audience never expected a realistic plot with logical transitions; it was precisely the artificial nature of the play that made Turandot’s transformation easier to accept. But Puccini and his librettists removed most of those elements from the storyline. Moreover, the composer made Liù’s death such an emotional climax that it would be difficult to surpass in the opera’s finale. Puccini, Simoni and Adami remained unable to resolve the dilemma. At one point they even turned to Arturo Toscanini, the influential conductor, in the hope that he would be able to suggest a way out of the impasse.

An abandoned opera

In autumn 1924, Puccini was found to have a tumour under the larynx, although he had in fact been suffering from throat complaints for quite some time. Late in November, the composer left for Brussels to undergo a new, experimental radiation treatment. He took the score of his opera and the sketches for the finale with him. On 29 November 1924, Puccini died of a heart attack, caused by complications from the treatment. At the time of his death, Puccini had completed writing the music for the opera, including the full orchestration, up to the point where the funeral procession with Liù’s body disappears into the distance – confirmation once again of how much of a challenge the finale was. Under one of the sketches, Puccini had written “poi Tristano”, a reference to Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. But at this point Adami and Simoni had not delivered a text for a long duet like in Wagner’s opera. Was Puccini pointing to Wagner’s ability to suggest a sublime, transformative power in music, something that was lacking so far in the finale for Turandot?

Puccini’s son Tonio, his publisher Tito Ricordi and the conductor Arturo Toscanini were determined to have the opera completed. They went in search of someone capable of taking on this difficult but also rather thankless task. After all, the composer who took charge of the completion of the opera would not only have to work out a convincing conclusion but would also need to suppress his own musical individuality as much as possible. In the end they chose the Neapolitan composer Francesco Alfano, a friend of Puccini’s who knew his style well and had recently written an exotic opera of his own, La leggenda di Sakùntala. His finale was to be published by Ricordi, one of the most prestigious publishing houses around the world

Criticism of Alfano

Alfano did his best to compose a cohesive and convincing final duet. He decided that if he was to make the ending more dramatically persuasive, he would need to largely ignore the sketches Puccini had left; he eventually used only a few of the more than thirty sketches available. To create room for the conflict and the change Turandot undergoes, Alfano composed his own music. When he sent the score to the publisher, the criticism was inevitably: too much Alfano, not enough Puccini. Toscanini in particular was furious that the composer had used so much of his own input. Toscanini wanted the end to be as close as possible to Puccini’s intentions, and he forced Alfano to cut his finale and make more use of Puccini’s sketches. The composer reluctantly agreed, although his new, shortened finale barely incorporated any more of Puccini’s material.

When Puccini’s final work premiered on 25 April 1926, the conductor Arturo Toscanini laid down his baton after the death of Liù in the middle of the third act, turned to the audience and said: “Here is where the opera ends because this is the point where the maestro died.” Alfano’s new finale was only included in the following performance. It was met with a critical reception. Not only was the ending unconvincing, but the orchestration also seemed feeble and unpolished in comparison with Puccini, who is at his most refined in this opera, showing the influence of composers such as Debussy, Strauss and Stravinsky. This was not entirely Alfano’s fault as he had only been able to see the complete score for the opera a few weeks before the deadline – too late to make stylistic changes to his finale. Despite the criticism, this would become the standard finale in performances of Turandot.

A continuing quest

In 2001, an alternative option appeared for the ending of Turandot, when the Italian composer Luciano Berio composed a new finale for the opera. Unlike Alfano, Berio drew on the material left behind by Puccini as much as possible, using a deft montage technique to combine it into a cohesive whole. But rather than trying to imitate Puccini, Berio added his own stylistic touch to the source material, including musical quotes from Wagner, Mahler and Schönberg. For the all-important kiss, which changes Turandot for good, Berio uses an orchestral intermezzo, deploying music to express what is almost beyond words. In contrast to the bombastic and somewhat kitsch final chorus in Alfano’s finale, Berio opts for a tranquil ending, a conclusion with a question mark.

We will never know whether Puccini would have eventually arrived at a satisfying finale and whether he would have found the right music to make the ending seem logical and correct. But there is also something appealing about that question mark: it opens up possibilities for conductors and stage directors to express their own preferences. Should they follow Toscanini’s example and go for silence, use one of Alfano’s two finales with their happily-ever-after message, or opt for Berio’s new finale that leaves room for the spectator’s own interpretation? Or perhaps they could take the plunge and come up with an entirely different ending? And so the artistic quest for a truly satisfying Turandot finale continues.

Text: Benjamin Rous

English translation: Clare Wilkinson

Turandot, Puccini and Orientalism

In a letter to his librettist Adami, Puccini suggests that the Chinese material in Gozzi’s play could use some Italian influences to make the opera appear more sincere to European audiences. This comment reveals an Orientalist viewpoint, in which the East is seen and deployed exclusively from a Western perspective. To what extent is this reflected in Puccini’s Turandot?

Turandot, Puccini en Oriëntalisme

“It is just possible that by retaining [the characters from Gozzi’s version] with discretion we should have an Italian element which, into the midst of so much Chinese mannerism – because that is what it is – would introduce a touch of our life and, above all, of sincerity.”

PUCCINI TO ADAMI

The term ‘Orientalism’ was conceived by the Palestinian-American scholar of literature, Edward Said. In his eponymous book Orientalism (1978), he criticises the way the East is stereotyped in the canonical literature and fine art of the West, as well as in political and academic discourses. According to Said, there is nothing innocent about the West’s perception of the Middle East, the Far East and North Africa. Preconceptions are produced and reproduced based on an idea of the East that the West has constructed; it has nothing to do with reality but is closely interlinked with colonialism and the associated unequal power relations.

Said gives the telling example of an account the nineteenth-century French author Gustave Flaubert wrote of his trip to Egypt. In it, Flaubert presents the Egyptian woman Kuchuk Hanem as a ‘typical’ oriental female: seductive, inscrutable and mysterious.

Underlying this European male view of Kuchuk Hanem was a relationship of power and dominance. For Said, this was the essence of Orientalism. The way ‘the Orient’ is ‘orientalised’ using such imaginary, racist and misogynist constructions is seen by Said as “a Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient”, enabling the West to exercise lasting colonial control over the East. Said’s exposure of the interconnection between racism, misogyny and colonialism prompted a wave of critical readings of the Western cultural canon.

Madama Butterfly and Turandot

Canonical operas did not escape such scrutiny either, and penetrating analyses in the academic literature laid bare their Orientalist worldview. Of Puccini’s operas, most attention has been directed at Madama Butterfly (1904) and Turandot (1926). Madama Butterfly tells the story of a Japanese geisha who is used and abandoned by the American Lieutenant Pinkerton. In these analyses, the stereotyping of Madama Butterfly as the naive ‘Other’ is seen as particularly problematic. The woman’s body that is first possessed and then rejected by a Western man symbolises the relationship European writers and composers have with their oriental subject matter.

The same connection between misogyny and Orientalism can be seen in Turandot. The female, oriental ‘Other’ is not so easily possessed in this story, but that only makes Prince Calaf all the more determined to have her – though the skies fall, as he puts it himself. Puccini’s decision to incorporate the Commedia dell’arte figures from Gozzi’s play as Ping, Pang and Pong in his opera also reflects his Western perception of the Orient. It should be noted that Puccini attached great importance to that individual perception. For example, he wrote to his librettists that while they should use Gozzi as the basis, they would benefit from drawing on their own powers of the imagination: only that would make the opera a real success. But it was precisely that imagination that left room for the influence of problematic ideas about the Orient – not least in the form of stereotypical names.

How Puccini and his librettists used their imagination to mould the characters into stereo-types of the Orient becomes particularly clear when we consider performances of Puccini’s opera. For example, as recently as 2016, Opera Philadelphia caused a scandal when it used ‘yellowface’ in an advertisement for Turandot. Moreover, the pseudo-Chinese splendour that marked traditional performances has become increasingly unacceptable because of its questionable overtones: given that Turandot is a mythical story rather than an account of a historical event, is there any justification for the traditional approach of a character laden with gold jewellery, with skin painted white, slit eyes and thin, arched eyebrows?

In the music

Puccini’s music can blind audiences to the more problematic aspects of the opera. However, the Orientalism is reflected not only in the libretto but also in the music, where Puccini produces his own version of the sounds of the East. Puccini’s use of oriental instruments such as a Chinese gong and a xylophone are not simply innocent attempts to create a Chinese atmosphere. Rather, these two instruments are used systematically to portray the Chinese people as cruel and barbaric. They are heard at the start of the opera, when the Mandarin reads out the horrific decree. From that point on, the two instruments are associated with beheadings. This association is reinforced a little later on in the score when Puccini introduces twelve double basses with the instruction for the music to be selvaggio (barbaric).

Puccini’s use of existing Chinese melodies has also been criticised as he incorporates them into a Western musical system that does not allow them to shine in their own right. In Madama Butterfly, this is because the Japanese melodies are repeatedly interrupted by the Western sounds of Pinkerton and his entourage, whereas in Turandot the process is more one of appropriation. For instance, Puccini repeatedly uses the traditional song Mo Li Hua (the ‘Jasmine Flower song’) to indicate the presence of Princess Turandot.

In the course of the opera, the melody is modified and adapted several times. For example, when Calaf claims victory over Turandot, he takes over this theme that was initially associated with the princess. In doing so, he demonstrates his dominance over her. In fact, this is precisely what Puccini does with the Mo Li Hua song – and what the composer struggled with, according to a letter he wrote to Adami: he twists the Chinese melodies until they fit his idea of the Orient. This is evident in particular in his use of Western tonality. Puccini’s unease is mainly due to the difficulty he experienced in ‘taming’ the Chinese melodies – just as Calaf tries to tame Turandot — and incorporating them in such a way that he retained control over the tunes.

Whispering

Puccini died before he was able to finish the opera. Franco Alfano wrote a triumphant finale to the opera, but it is not included in the present production. Barrie Kosky’s stage direction also recognises that there are enough orientalist elements in the music without any need to replicate them in the staging. What we can find on the stage is a large mirror – or several mirrors – in which we see ourselves reflected as a Western audience: to what extent do we harbour fears and obsessive desires for the ‘Other’ and how far do we want to go to control them?

Text: Eline Hadermann

English translation: Clare Wilkinson

SOURCES:

- Said, Edward. Orientalism: Western conceptions of the Orient. 1995, Penguin Books.

- Liao, Ping-hui. “‘Of Writing Words for Music Which Is Already Made’: Madama Butterfly, Turandot, and Orientalism”. Cultural Critique No. 16 (Autumn, 1990), pp. 31-59, University of Minnesota Press.

- Busher, Rob. “Turandot: Time to call it quits on Orientalist Opera?” Opera Philadelphia. https://www.operaphila.org/backstage/opera-blog/2016/turandot-time-to-call-it-quits-on-orientalist-opera/

From Puccini’s letters to Giuseppe Adami

In 1928, Puccini’s friend and librettist Giuseppe Adami published a collection of Puccini’s letters. These letters, all addressed to Adami, give a unique insight in Puccini’s creative struggles as he worked on Turandot.

From Puccini’s letters to Giuseppe Adami

Spring 1920

I do not feel like coming to Milan just now. It is better that we see each other later on – you must prepare an outline. Do not hurry it. You must ponder it well and fill it out with details and embellishments. Make Gozzi’s Turandot your basis, but on that you must rear another figure; I mean – I can’t explain! From our imaginations (and we shall need them) there must arise so much that is beautiful and attractive and gracious as to make our story a bouquet of success. Do not make too much use of the stock characters of the Venetian drama – these are to be the clowns and philosophers that here and there throw in an jest or an opinion (well chosen, as also the moment for it), but they must not be the type that thrust themselves forward continually or demand too much attention.

Spring 1920

Immediately on the receipt of your express letter today I wired to you on a first impulse, advising the exclusion of the masks. But I do not wish this impulse of mine to influence you and your intelligence. It is just possible that by retaining them with discretion we should have an Italian element which, into the midst of so much Chinese mannerism – because that is what it is – would introduce a touch of our life, and above all, of sincerity. The keen observation of Pantaloon and Co. would bring us back to the reality of our lives. In short, do a little of what Shakespeare often does, when he brings in three or four extraneous types who drink, use bad language, and speak ill of the King. I have seen this done in The Tempest, among the Elves and Ariel and Caliban.

But these masks could possibly also spoil the opera. Suppose you were to find a Chinese element to enrich the drama and relieve the artificiality of it? So I come to the conclusion that for the moment I am adding neither salt nor pepper. I leave it to you and may the good God give you inspiration!

October 1921

Turandot gives me no peace. I think of it continually, and I think that perhaps we are on the wrong track in Act II. I think that the duet is the kernel of the whole act. And the duet in its present form doesn’t seem to me to be what is wanted. Therefore I should like to suggest a remedy. In the duet I think that we can work up to a high pitch of emotion. And to do so I think that Calaf must kiss Turandot and reveal to the icy Princess how great is his love.

After he has kissed her, with a kiss of some – long – seconds, he must say “Nothing matters now. I am ready even to die,” and he whispers his name to her lips. Here you could have a scene which could be the pendant to the grisly opening of the act with its “Let no one sleep in Pekin.” The masks and perhaps the officials and slaves who were lurking behind have heard the name and shout it out. The shout is repeated and passed on, and Turandot is compromised. Then in the third act when everything is ready, with executioner, etc., as in Act I, she says (to the surprise of everyone), “His name I do not know.” In short, I think that this duet enriches the subject considerably and raises it to an emotional interest which we have not now attained. What do you think of it? Tell Simoni. (1)

My life is a torture because I fail to see in this opera all the throbbing life and power which are necessary in a work for the theatre if it is to endure and hold.

November 1921

That first act – I am sure of it – is good. Why don’t you get on? We must get it finished, and successfully. I have some ideas, extravagant perhaps, but not to be despised. The duet! The duet! It is the meeting-point of all that is decisive, vivid and dramatic in the piece.

November 1922

I am so sad! And discouraged too. Turandot is there with the first act finished, and there isn’t a ray to pierce the gloom which shrouds the rest. Perhaps it is wrapped forever in impenetrable darkness. I have the feeling that I shall have to put this work on one side. We are on the wrong track for the rest of the opera. [...] The basis of the act must be the duet. Let this be as fantastic as possible, even if you should exaggerate. In the course of this grand duet, as the icy demeanour of Turandot gradually melts, the scène, which may be an enclosed place, changes slowly into a spacious setting enriched with every fantastic adornment of flowers and marble tracery, where the crowd and the Emperor with his Court, in all the pomp of an important occasion, are waiting to welcome Turandot’s cry of love. I think that Liù must be sacrificed to some sorrow, but I don’t see how to do this unless we make her die under torture. And why not? Her death could help to soften the heart of the Princess… I am tossed in a sea of uncertainty. This subject is causing me tremendous anxiety of spirit. I wish that both you and Renato would come here! We could talk it over and perhaps save the whole thing. If we go on as we are doing, requiescat Turandot!

December 1923

I need the duet urgently. Try to strengthen it a bit. Keep the motives which we have decided upon and which are the essential ones, but if you can find some new elements to make it more interesting, so much the better.

January 1924

We have the first, second and third versions to work on, and from these three we shall construct the great duet. Between us, understanding each other as we do, and with such a quick worker as you are, we shall soon produce the final version. I should like to return to the idea of internal voices to illustrate psychological moments.

September 1924

We must meet. If you come here we shall fix things up. Bear in mind also our first idea of introducing internal symbolic voices, speaking of liberation for the love which is coming to birth and helping and encouraging it. It must be a great duet. These two almost superhuman beings descend through love to the level of mankind, and this love must at the end take possession of the whole stage in a great orchestral peroration. Well, then, make an effort. Come!

October 10, 1924

Is it really true that I am not to work any more? Not to finish Turandot? There was so little still to do for the successful completion of the famous duet. Come, come, dear little Adami, do me this favour, make me the great effort of devoting two or three hours to me and send me the lines which I need. But do this little piece of work in such a way that it will be final and not have to be returned again. Don’t disappoint me!

October 22, 1924

What am I to say to you? I am going through a terrible time. This trouble in my throat is giving me no rest, although the torment is more mental than physical. (2) I am going to Brussels to consult a well-known specialist. I am setting out very soon. I am waiting for a reply from Brussels and for Tonio’s return from Milan. (3) Will it be an operation? Or medical treatment? Or sentence of death? I cannot go on any longer like this. And then there’s Turandot. Simoni’s verses are good, and I think he has done just what was needed and what I had dreamed of. All the rest of Liù’s appeal to Turandot was irrelevant, and I think your opinion is correct that the duet is now complete. Perhaps Turandot has too much to say in that passage. We shall see – when I get to work again on my return from Brussels.

(1) Renato Simoni was Giuseppe Adami’s co-librettist on Turandot.

(2) The trouble had been diagnosed as cancer, but Puccini himself had not been told this.

(3) Tonio was Puccini’s son and secretary.

programmaboek

Become a Friend of Dutch National opera

Friends of Dutch National Opera support the singers and creators of our company. That friendship is indispensable to them and we are happy to do something in return. For Opera Friends, we organise exclusive activities behind the scenes and online. You will receive our Friends magazine, have priority in ticket sales and a 10% discount in the Dutch National Opera & Ballet shop.