Giulio Cesare online programme

Performance information

Voorstellingsinformatie

Performance information

Duration

3 hours and 45 minutes, including one interval

The opera is sung in Italian.

Dutch surtitles based on the translation of Jan Herman.

English surtitles based on the translation of Kenneth Chalmers.

Makers

Libretto

Nicola Francesco Haym

Conductor and harpsichord

Emmanuelle Haïm

Director

Calixto Bieito

Set design

Rebecca Ringst

Costume design

Ingo Krügler

Lighting design

Michael Bauer

Video design

Sarah Derendinger

Dramaturgy

Bettina Auer

Cast

Giulio Cesare

Christophe Dumaux

Curio

Georgiy Derbas-Richter*

Cornelia

Teresa Iervolino

Sesto

Cecilia Molinari

Cleopatra

Julie Fuchs

Tolomeo

Cameron Shahbazi

Achilla

Frederik Bergman

Nireno

Jake Ingbar**

* Dutch National Opera Studio

** Associate artist of Dutch National Opera Studio

Le Concert d’Astrée

Coproduction with Gran Teatre del Liceu (Barcelona)

Production team

Assistant conductor

Simon Proust

Assistant director

Astrid van den Akker

Debora Regoli

Assistant director during performances

Astrid van den Akker

Rehearsal pianists

Benoît Hartoin

Ernst Munneke

Language coach

Rita De Letteriis

Assistant set design

Annett Hunger

Assistant video

Clarisse Perrion

Video technician

Rutger Flierman

Special Effects

Ruud Sloos

Koen Flierman

Costume supervisor

Mariama Lechleitner

Stage managers

Merel Francissen

Marjolein Bergsma

Emma Eberlijn

Thomas Lauriks

Artistic affairs and planning

Sonja Heyl

Orchestra representative

Mélodie De Keukelaere

Orchestra inspector

Maxime Fabre

Master carpenter

Wim Kuijper

Lighting manager

Peter van der Sluis

Props manager

Niko Groot

First dresser

Sandra Bloos

First make-up artist

Isabel Ahn

Sound technician

Florian Jankowski

Dramaturgy

Jasmijn van Wijnen

Surtitle director

Eveline Karssen

Surtitle operator

Irina Trajkovska

Set supervisor

Mark van Trigt

Production management

Emiel Rietvelt

Le Concert d’Astrée

First violin

David Plantier

Elisabet Battaler

Maria Gomis

Maud Giguet*

Rozarta Luka

Sandrine Dupé

Valentine Pinardel

Yan Ma

Second violin

Clémence Schaming

Emmanuel Curial

Isabelle Lucas

James Jennings

Jeanne Mathieu

Myriam Cambreling

Yuki Koike*

Viola

Delphine Millour*

Diane Chmela

Jean Luc Thonnérieux

Laurence Duval

Martha Moore

Cello

Annabelle Luis*

Emily Robinson

Jennifer Hardy Bregnac

Julien Hainsworth**

Mathurin Matharel**

Double bass

Elise Christiaens

Elodie Peudepiece

Gabriele Basilico**

Marie-Amélie Clément

Recorder

Emma Huijsser

Stefanie Troffaes

Traverso

Stefanie Troffaes

Oboe

Gilles Vanssons

Yann Miriel*

Bassoon

Emmanuel Vigneron

Philippe Miqueu*

Horn

Antonia Riezu

Christopher Price

Jeroen Billiet (solo)

Pieter d’Hoe

Lute

Magnus Andersson**

Shizuko Noiri* **

Viola da gamba

Marion Martineau*

Harp

Emma Huijsser*

Harpsichord

Emmanuelle Haïm**

Benoît Hartoin**

* (also) on stage

** basso continuo

Extras

Frans Dam

Anton van der Sluis

Yannick Jhones

Maurits van der Roest

Isak Verkaik

The story

Follow the link below to read the story of Giulio Cesare.

The story

I

Giulio Cesare (Julius Caesar) and his army have chased his rival and former political ally Pompeo (Pompey) into Egypt, where Pompeo has sought support from Tolomeo (Ptolemy), the king of Egypt and brother of Cleopatra. When Cesare arrives, Pompeo’s wife Cornelia begs mercy for her husband. Cesare agrees on condition that he is recognised as Egypt’s leader, but Cornelia’s plea comes too late: Tolomeo has had Pompeo beheaded. Tolomeo’s counsellor Achilla brings Cesare the head of the dead man as a gift to welcome him. Cesare is appalled. Cesare’s lieutenant Curio falls in love with Cornelia and plots revenge together with Sesto, Cornelia’s son.

Cleopatra wants to become queen of Egypt in her own right, so she seeks to manipulate Cesare for her own ends. She embarks on a campaign to seduce him, approaching him in the guise of the lady-in-waiting Lidia. Cesare is captivated by her beauty and resolves to assist her.

When Cesare and Tolomeo meet up as politicians and leaders, the atmosphere is febrile. Tolomeo is highly impressed by Cornelia, whom he has actually promised to Achilla as his wife.

II

Once again, Lidia/Cleopatra utilises all her charms in her attempt to seduce Cesare. Meanwhile, both Achilla and his rival Tolomeo woo Cornelia assiduously, but she rejects both suitors. Sesto prevents his mother from killing herself. Nireno has a plan that will enable Sesto to kill Tolomeo. When Cesare finds himself alone with Lidia/ Cleopatra, he declares his love. Their idyllic tryst is disturbed by Curio, who warns of a conspiracy against Cesare. Cesare decides to confront his enemies. Cleopatra throws off her disguise and responds to Cesare’s declaration of love.

Sesto’s attempt to kill Tolomeo is thwarted by Achilla, who brings news that Cesare, seeing no way out, has jumped into the sea and drowned.

Cleopatra decides to fight on the side of the Romans to revenge Cesare’s death. After discovering that Tolomeo has deceived him, Achilla too joins the Romans to fight against Tolomeo.

III

Tolomeo’s troops defeat Cleopatra’s army. He captures his sister and plans to have her executed.

Achilla dies in the battle, but it turns out Cesare is still alive. He promises to rescue Cleopatra and Cornelia from the clutches of Tolomeo. Cesare frees Cleopatra. When Tolomeo renews his attempts to win Cornelia’s heart, Sesto finally manages to kill him.

Cesare crowns Cleopatra as queen of Egypt and she pledges her allegiance to Rome in gratitude.

Text: Bettina Auer and Jasmijn van Wijnen

Translation: Clare Wilkinson

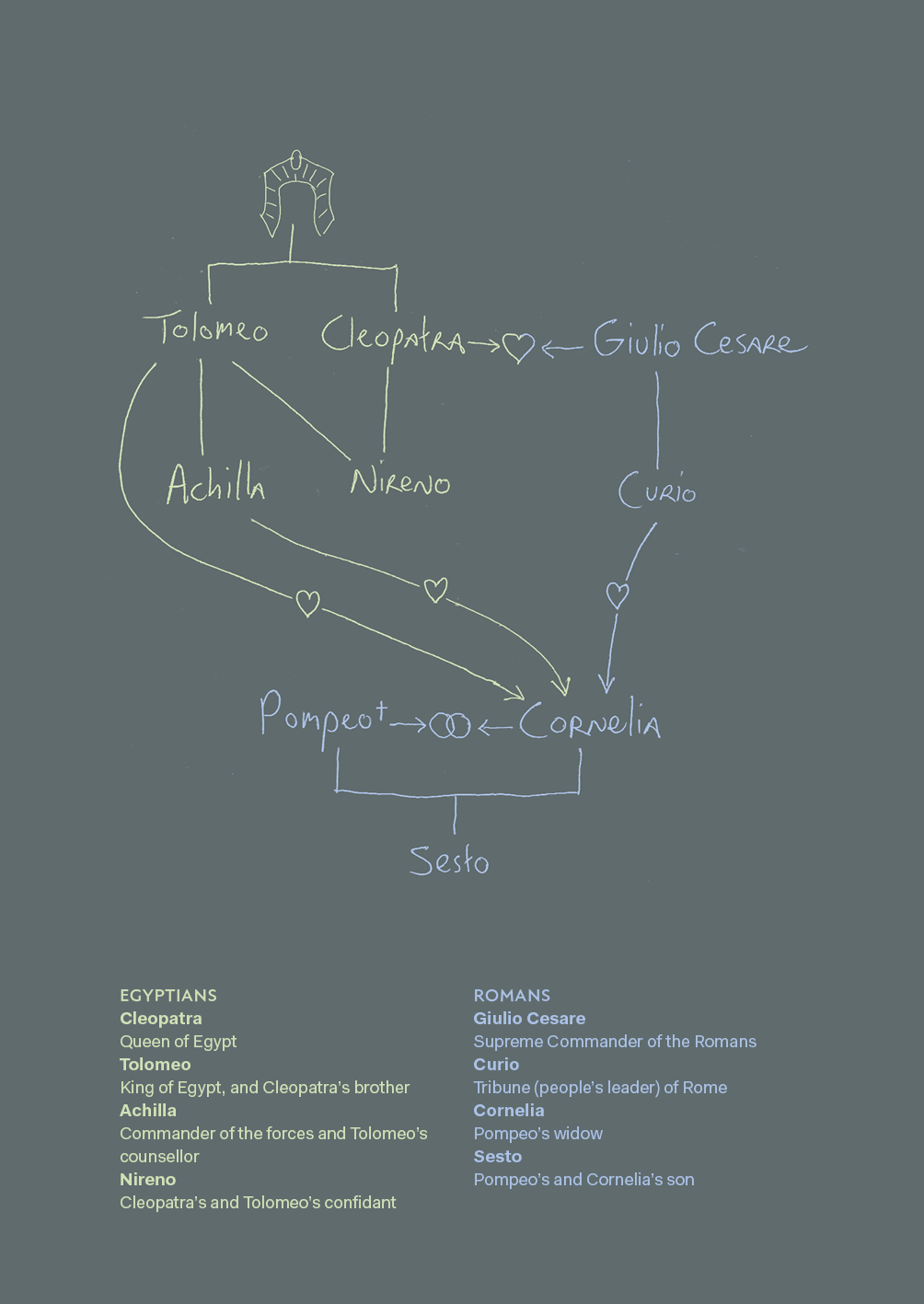

Characters and their relationships

personages en verhoudingen

Characters and their relationships

Handel came, saw and conquered

How a German won over London with Italian operas.

Handel came, saw and conquered

In the early eighteenth century, London fell under the spell of the Italian opera. The first high point was the production of Handel’s Rinaldo in 1711. At the time, Handel was in the service of the Elector Georg I Ludwig of Hanover. When the Elector ascended the English throne as George I several years later through a complex dynastic path — the English needed a Protestant monarch — Handel followed him to London. But there was no question of a foreign composer holding a position in the English court. Handel kept his options open and angled for a vacancy in Hamburg, but the English establishment had no intention of letting this golden boy go so easily. Born in Halle in Saxony as Georg Friedrich Händel, and known as Giorgio Federico Hendel or il caro Sassone during a four-year stay in Italy, it was as George Frideric Handel that he was destined to make a lasting mark on the music scene in England.

Royal Academy

In 1719, a group of English aristocrats founded the Royal Academy of Music with the express aim of establishing Italian opera on a firm footing in London. Previous attempts had invariably ended in bankruptcy, not least because of the sky-high fees charged by the star soloists. The founders were officially investors and shareholders, but they are unlikely to have expected much of a profit from the enterprise; in the nine seasons that it was in operation, the Academy only once paid a dividend. The Royal Academy founders were above all opera lovers, who had got to know Italian opera during their Grand Tours and wanted continued access to performances of the highest quality after their return to England.

Despite its name, the Royal Academy was not an official royal institute in the French mode. However, the monarch offered his patronage and a contribution of 1,000 pounds, a sufficient amount to pay Handel for one season but not enough for a top castrato or a prima donna — they could easily cost twice that.

Vocal scout

Handel was appointed “Master of the Orchester with a Sallary”, a somewhat vague title that did not reflect his wide range of responsibilities. He soon developed into what we would probably call an ‘artistic director’. His duties included vocal scouting, dramaturgy, decor, costumes, planning and negotiating contracts, all tasks for which modern-day opera houses have entire departments. Before the first season, Handel was sent to the continent to recruit singers. In particular, he was given an explicit order to engage the famous castrato Carlo Boschi, better known as il Senesino. He was allowed to splash out because the London endeavour was doomed to failure without a top castrato. Boschi was duly hired from the second season onwards for 2,000 pounds a year.

But we should not forget Handel’s most important contribution to the whole enterprise (from our perspective at any rate): in the course of the Academy’s nine seasons, he composed the music for thirteen operas. A further eight and seven operas respectively were composed by the Italians Giovanni Bononcini and Attilio Ariosti.

Giulio Cesare: sensuality and power

Handel wrote only one opera in his fifth season at the Royal Academy: Giulio Cesare in Egitto (Julius Caesar in Egypt). He was doing very well for himself by then. He had obtained a position at court after all for 400 pounds per annum and he had just moved to a fine house in Brook Street.(1) What is more, the previous season he had managed to engage the famous prima donna Francesca Cuzzoni. London was very excited about her arrival, even if the local press did spell her name as ‘Mrs Cotsona’.

Now aged thirty-eight, Handel was at the peak of his artistic powers and with Giulio Cesare he wrote one of his best and most popular operas. The combination of politics and passion in a familiar yet exotic historical context gave Handel and his librettist Nicola Francesco Haym the perfect ingredients for a major hit. Haym was also a composer and regularly played in the orchestra as a cellist. In addition, he was the secretary of the Royal Academy from 1722 and he was the stage manager responsible for affairs both on stage and backstage — there was no actual stage director in those days.

Born in Rome, Haym was skilled in adapting Italian libretti for London audiences. As usual, he based his libretto on an existing text. The original libretto by Giacomo Francesco Bussani had been set to music by Antonio Sartorio and had already been performed several times in Venice and Milan. Haym changed it to suit London tastes, for example by removing the comic wet nurse, a regular feature of Venetian operas since the days of Monteverdi and Cavalli. He also condensed the recitatives considerably as the audiences in London did not speak Italian.

Londoners were, however, familiar with the context of the story, which takes place during Julius Caesar’s trip to Egypt in 48-47 BC. But as in Shakespeare or Hollywood, the historical background was simply the pretext for a fictional plot.

(1) Later, Jimmy Hendrix lived next door to Handel’s house in Brook Street. It is now the site of the Handel & Hendrix in London Museum, which will open in May 2023.

Four horns

Even so, it was mainly Handel’s musical genius and his infallible theatrical instinct that made Giulio Cesare a masterpiece. All the signs are that he wanted to create something out of the ordinary. In the six months he spent working on the opera in close cooperation with Haym, he repeatedly made major changes. The multi-faceted expressiveness of the opera is unique. The plot has pace and alternates between intimate moments and spectacular scenes, while Handel composed one impressive aria after another. Formally Giulio Cesare is an opera seria that deals with a tragic clash of ambitions and the supremacy of fate, but there are also comic elements that act as a contrast to the main story.

The opera starts with the usual French overture: a grand introduction followed by a faster fugue-like section. In Handel’s day, the overture was played with the curtains closed. Also, unlike later, for example with Mozart, there was no connection either dramatically or musically with the actual opera. But Handel broke with that tradition. In Giulio Cesare, the overture segues seamlessly into a minuet-like dance, which in turn ends in a chorus (sung by the soloists in Handel’s day) welcoming Cesare to Egypt. Without realising it, we are already in the midst of the story. This choice, together with the use of no fewer than four (!) horns, still an unusual instrument in the orchestras of the day, shows that this was no run-of-the-mill opera.

Goosebump arias

Cesare announces his arrival in the first short aria, with vocal fireworks we can expect from the rest of the opera too. But Handel has more strings to his bow musically, and more colours in his orchestral palette. The strength of this opera lies in the great range of feelings and the psychological depths that Handel gives to his characters. We see Cesare as a military hero, a lover and a philosopher. But the opera could equally have been titled Cleopatra because Handel created one of his finest roles in the Egyptian queen. She is portrayed not only as a powerful stateswoman but also as a calculating seductress who eventually falls tragically in love. To express this, Handel gives her two of his loveliest goosebump arias, ‘Se pietà di me non senti’ and ‘Piangerò’, a lament unusually set in the key of E major.

Handel pulled out all the stops to convey the nuances in the interaction between his characters. For instance, at the start of the second act, a flirtatious Lidia/Cleopatra pre-sents herself as Virtue in the aria ‘V’adoro pupille’, surrounded by the nine Muses. For this alluring scene, Handel adds an orchestra of nine instruments on the stage — an oboe, two violins, a viola, a viola da gamba, a theorbo, a harp, a cello and a bassoon — in addition to the muted strings in the pits. It is an outstanding example of multi-coloured Baroque orchestration.

The four horns in the opening chorus return several times later on, including in the final chorus. Caesar’s aria ‘Va tacito e nascosto’, which is about a cunning hunter, includes a long horn solo, the only one in any of Handel’s operas, to accentuate the association with hunting.

Reception

When Giulio Cesare premiered in the King’s Theatre at the Haymarket on 20 February 1724, it was a huge success. That was largely thanks to the top-notch cast, with il Senesino in the title role and Francesca Cuzzoni singing Cleopatra. Both were known for being difficult, and to avoid any arguments Handel was forced to give them precisely eight arias each and one long recitative with orchestra accompaniment (recitativo accompagnato).

The opera was performed thirteen times in its first season, and ten times the following year. To put this into perspective, five to six performances would generally have been seen as a sign of success. The opera returned in 1730 and 1732, with changes each time to accommodate the new cast. For example, in 1730 Handel composed two arias for his new favourite soprano Anna Maria Strada del Po (la Stradina), who of course sang the role of Cleopatra. Giulio Cesare also travelled abroad. As early as the premiere year, a concert version was performed in Paris. Staged productions followed in subsequent years in Hamburg and Braunschweig.

Revival

The first modern performance was in 1922 in the German university town of Göttingen, the cradle of the Handel revival. Art historian, music scholar and amateur musician Oskar Hagen had made drastic changes to the score. The text was translated into German and the castrato role of Cesare was sung by a baritone. The first ‘historically informed’ performance took place in 1985, in a production conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt during the Wiener Festwochen.

Nowadays, Giulio Cesare is Handel’s second most frequently performed work after the Messiah. Handel is also the only Baroque composer in the top ten most frequently performed opera composers, a list that otherwise consists of names such as Mozart, Rossini, Verdi, Wagner and Puccini.

Oratorio

Handel’s Giulio Cesare is undoubtedly a masterpiece. Clearly, his creative juices were flowing because two more outstanding works followed in the next twelve months, namely Tamerlano and Rodelinda. At the same time, the enthusiasm in London for Italian opera was starting to wane. The deathblow was the immense success in 1728 (with sixty-two performances!) of The Beggar’s Opera by John Gay and Johann Christoph Pepusch, an English-language, merciless take-off of the Italian style.

But quite apart from changes in taste, there was no viable business model for Italian opera, in particular because of the exorbitant fees demanded by the star soloists. The Royal Academy ceased operating in 1728, but Handel joined forces with a few colleagues to relaunch the company, which lasted another five years in its revised form. Meanwhile, a group of aristocrats had founded a rival opera company called the Opera of the Nobility, with Nicola Porpora as the musical leader. They were able to steal several of Handel’s star soloists and also managed to engage Farinelli, the superstar of the Italian castrati. Handel saw which way things were heading and so he increasingly focused on the genre of English-language oratorios. Once again, he scored success with works such as Israel in Egypt, Samson and the Messiah, which have had a lasting influence on English music.

Text: Jan van den Bossche

Translation: Clare Wilkinson

‘Which Giulio Cesare do you do?’

In conversation with conductor Emmanuelle Haïm.

‘Which Giulio Cesare do you do?’

The conductor and harpsichordist Emmanuelle Haïm talks about what preparing a Handel opera involves, the theatrical side of Handel as a composer and historically informed performances of the Baroque repertoire.

“A lot needs to be figured out,” says Haïm as she starts to explain what happens in the initial musical rehearsals for a Handel opera. “As a composer, Handel was very focused on the drama, so the plot is the determining factor in his work. The choices for the form of an aria or a recitative, with or without accompaniment, are always grounded in considerations of the plot and dramatic requirements. Each aria is designed to emphasise the emotional state of the character at that specific point in the action. That is why we rarely work on a single aria in isolation. You need to carefully track the path of each character from start to finish to understand where they are coming from and where they are headed — to follow that character’s journey in the course of the opera.” That is why the rehearsal period for Giulio Cesare started with a read-through of the entire opera, after which each singer zoomed in on their own texts in more detail. “What does the character sing and how are certain arias structured? What does a specific aria mean for the singer? And what do I think it means from my particular perspective?”

Arias in Baroque operas are known for their ABA, or da capo, form: the first section of the aria is repeated at the end, with room in the repeated section for the singer to demonstrate their vocal skills by adding their own ornamentation. Such arias are not so much about sharing information concerning developments in the storyline; instead, they allow space for a single idea and emotion to be elaborated on, supported by the various colours in the music. “In Handel’s day, individual ornamentation was very important for the singers. They were trained from a young age to sing with as much virtuosity as possible, and of course they wanted to demonstrate what they could do. They were given the freedom to do this in these arias, as the final section allowed the singers to show off their artistry. I explore this aspect of the arias in the first stage of the musical rehearsals in close collaboration with the singers. I write out an ornamented passage of music, the singer is given room to suggest alternative choices and together we decide which version is most powerful and most appropriate for the content.”

As well as the arias, there are long sections of recitative, which serve to propel the plot. “The recitative should be a kind of sung speech, and the words should be enunciated as naturally as possible. A language coach helps with that, and we also look at what the texts mean and how the voice can be used to best convey that meaning.”

Historically informed

“There is an enormous amount of historical documentation explaining the endless ways of performing a trill or appoggiatura. In Handel’s day, these were well-known conventions but that is no longer the case today. We carry out historical research to figure out exactly what is meant by the documented information.” Musical performances are always subject to change, but this was specifically the case in Handel’s time. Handel wrote the roles with certain singers in mind and the arias would be rewritten when the cast changed. That is one reason why there are so many different versions of the same opera. “In fact, Giulio Cesare is not so much one opera as many different operas in one. The question should really be which Giulio Cesare do you do? It is incredibly inspiring to delve deep into the source material. We’re fortunate that a lot has already been researched and written about Handel.” This is the fourth time Haïm has conducted Giulio Cesare, but she never tires of the music. “There are some composers you can never get enough of: Bach, Mozart, Monteverdi, Handel… Every time I approach their music again, I bring my own experiences to the piece and I discover something new.”

A new context, a new form

Choices have to be made for each new production of Giulio Cesare. That is in part because the context in which the work was performed originally was so different to the situation today. “People experienced operas in a very different way in Handel’s time. They would drink, eat and chat during the performance. The perception of time was quite different to now, where the audience sits in a darkened theatre concentrating fully on the performance. How many intervals are needed, for example? That too is a question that needs addressing.”

Not only has a visit to the opera changed in nature, the layout of the theatrical space has also altered completely. Now the orchestra’s musicians play in the pit facing the audience, with a conductor who has their back to the auditorium. “In Handel’s time, the musicians faced the singers and the conductor stood with his back to the musicians. He was essentially conducting the singers, while the orchestra followed the singers. Everyone was on a much more equal footing.” Indeed, with Giulio Cesare it is not unusual for Emmanuelle Haïm to play the harpsichord as well as conduct. “That feels very natural for me. The musicians, especially the continuo players who accompany the recitatives, need to follow the singers, so a conductor standing in between them waving away would only be a distraction. You need a direct connection between the musician and the singer. The continuo passages are a permanent process of interpretation, and the singer and harpsichordist need to be in sync.”

The approach to Giulio Cesare is informed by historical research, but the opera is performed in the here and now. The music can never sound exactly the same as it would have originally, and that is not the intention either. “It isn’t a historical reconstruction, it’s a historically informed performance practice.” Taking that point of departure, all members of Haïm’s orchestra, Le Concert d’Astrée, carry out their own research into historical performance practices. “One of my harpists, for example, has nearly finished a study of the use of the harp in continuo passages, while one of my violinists is investigating the posture for playing the violin in the early seventeenth century. It is not the case that you can’t play Bach on a piano or accordion, because the music holds up fine. But if you play Bach on a harpsichord, the instrument more or less teaches you how to play the music. That’s why research is so enriching.”

Because Giulio Cesare can take on so many different forms, the artistic team enjoys a great deal of freedom. “Stage directors have clear ideas about the dramatic arc and the key points in the story. Where do we want to approach the key moment relatively quickly and where do we want to take our time?” Such decisions are taken in close consultation between the musical leader, the dramaturg and the director. “You need to be a team player to produce an opera,” says Haïm.

The instrumentation

In addition to the three countertenors in the cast of Giulio Cesare, who take on the roles originally intended for castrati, another striking feature of this masterpiece is Handel’s instrumentation. “Many of Handel’s operas have a string quartet, oboes, bassoons and a continuo group consisting of two harpsichords and a lute or theorbo. Recorders (originally played by the oboists) also have a prominent role in Giulio Cesare: they can be heard both in an aria sung by Cornelia and one by Sesto. Then there is the traverso (the wooden predecessor of the modern flute), which is used in Cleopatra’s famous aria ‘Piangerò la sorte mia’, giving it a delicate colour.” The relatively large horn section (four, two for the lower parts and two for the higher parts) is also unusual.

But it is not only the non-standard variation of instruments that makes the opera stand out. In one of the opera’s most remarkable scenes, Handel creates a kind of performance within a performance. “The Parnassus scene in which Cleopatra appears in the guise of Virtue with the aim of seducing Cesare is a very interesting reference to the past. Cleopatra appears on stage with an orchestra of nine Muses, the deities of art and science from Graeco-Roman antiquity. The music that Handel has composed is delightful, as the little orchestra of Muses on the stage and the orchestra in the pitreact to one another. For this scene, Handel has included instruments that in his day had come to be seen as ‘old instruments’, namely the viola da gamba and the Baroque harp.” They encircle Cleopatra like a musical halo and intensify the seduction scene, whereby the scene does not just refer to Roman antiquity in its content, but also points to the past in its choice of instruments.

Ancient tales for the present day

The various stories that have been told about Julius Caesar and Cleopatra are closely connected to themes such as the struggle for power, seduction and war — issues that were highly topical in Handel’s time. “The way they took that story, rewrote it and turned it into a tale relevant to their own day is in fact a very modern approach to the past,” concludes Haïm. That same mechanism can be seen at work in Calixto Bieito’s contemporary staging of the opera. Both the musical performance and the dramaturgical concept are informed by the past, to enhance the relevance of the opera for the present day.

Text: Jasmijn van Wijnen

Translation: Clare Wilkinson

Caesar and Cleopatra in a high-tech desert paradise

In conversation with Calixto Bieito and dramaturg Bettina Auer.

Caesar and Cleopatra in a high-tech desert paradise

How relevant is the storyline of an opera from 1724 to modern-day audiences? Incredibly relevant, say Calixto Bieito and Bettina Auer. In this interview, they talk about the main themes and explain why we are still fascinated today by a story brimming with political intrigue and lust for power, and centred on the question of how much you are willing to stake on getting what you believe you deserve.

“To start with, Giulio Cesare has wonderful music and it is an amazing piece of theatre all about politics, power and sex,” says Calixto Bieito. “It’s sensual. The opera has all the necessary ingredients for a fantastic production. It’s a veritable masterpiece.” The director has mentioned the two main themes in Handel’s opera: love and politics. “Isn’t every love story about power to some extent?” ponders Bieito. “Does Cesare want to marry Cleopatra because she will bring him more success in life, or because he is in love with her? We still see this tension today in all kinds of contexts.”

“Giulio Cesare is about how far you would go to obtain power,” adds the dramaturg, Bettina Auer. “How far would you be willing to go? Would you be prepared to insult someone, humiliate them, even kill them? It’s also about a political game in which the players change their stances depending on the situation. Initially, Cesare was Pompeo’s political ally but at the start of the opera Pompeo has become Cesare’s opponent and has been chased all the way to Egypt.” In his stage direction, Bieito particularly emphasises the figurative masks all the players wear: “There is an awful lot of flattery. That’s the art of politics: it is the ability to be manipulative, to orchestrate and control emotions and conflicts.”

“You could in fact compare Giulio Cesare to a series like House of Cards, which is set in present-day America,” suggests Auer. “The relationship between Cesare and Cleopatra is also reminiscent of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth: she manipulates him and he manipulates everyone.” That raises the question of whether Cesare and Cleopatra are truly in love. “I don’t know,” says Bieito firmly, “and I want to keep it ambivalent. The best lie is the truth.”

Observation without commentary

The focus in Bieito’s production is wealth, riches that are celebrated and dreamed about, and a boundless lust for power. He sets the opera in a modern-day unnamed oligarchical society, a high-tech paradise built up from nothing in the desert. In his direction, he shows us the comings and goings of the super-rich – the people who crave power, money and status. “But I don’t criticise them. I feel more like a kind of Ödön von Horváth (1), in the sense that I present an observation on the stage without passing judgement.” Bieito drew inspiration from his work for the international exhibition Expo 2008 in Zaragoza, Spain. He directed the opening ceremony in Zaragoza, where he found himself in a world of extremes, ostentatiousness, luxury and wealth. “Everything there was fantastic. Every country put on its best face.”

As its title suggests, the libretto of Giulio Cesare in Egitto is set in Egypt, at the court of Tolomeo and Cleopatra. In Bieito’s stage direction, the new setting is deliberately left vague, but it is reminiscent of the absurdity and artifice of a Qatar-like environment where everything seems possible while the negative aspects are glossed over. The stage decor was based quite directly on the Saudi Arabian pavilion at the Expo 2020 in Dubai. Bieito describes the world in which he has set Giulio Cesare as “a digital dream world in a desert paradise”. Video clips by Sarah Derendinger are projected on a huge box, covered with LED lights and screens, that takes up a variety of positions on the stage. “That adds a surrealist layer to the whole thing,” explains Auer. According to Bieito, “The images refer to dreams, fantasies and the subconscious”.

(1) Ödön von Horváth (1901-1938) was a Hungarian-German novelist and playwright. He claimed he never wrote comedies — the humour in his plays was merely an accurate rendition of the excruciating absurdity of the real world.

Absurdly rich

“I heard that the next Winter Olympics are due to be organised in Saudi Arabia,” says Bieito. “Which is obviously absurd. I want to show the absurdity of wealth, that picture of endless possibilities. Being able to lie on your private beach but still choosing to eat the cheapest ice cream. Or being able to buy a town. It’s a bit like Mahagonny.” But here too, “This is not a criticism of Saudi Arabia,” stresses Auer. “We show a world that is different to ours, a world of extreme wealth.” “A world like the Egypt of Tolomeo and Cleopatra — that was also a place of exceptional affluence,” says Bieito. Auer adds: “We’re referring to an impression that we all have of countries like this due to all the images we have absorbed over time, be it consciously or unconsciously.”

The juxtaposition between the East and the West, which is an inherent aspect of Giulio Cesare, is not emphasised on the stage. “The opera was written from an imperialist perspective,” explains Auer. “Handel shows the Romans on the one hand as sovereign, if also arrogant, and the Egyptians on the other hand as barbarians. Of course, English audiences at the time would have identified with the Romans, the Europeans. But that isn’t our point of view. Our production doesn’t show the Roman people versus the Egyptian people; you see a group of elite individuals wrestling for power.”

Primitive emotions in a high-tech world

“There’s an element of barbarism in all of us,” argues Bieito. “We all have these primitive emotions deep down. It’s a natural part of us, an aspect that surfaces in situations that revolve around power and control. That’s why there are a few violent scenes in the production.” He can count on a fantastic cast with impressive stage personalities for these scenes, in which the singers have to draw on their innermost selves. “I love working with these singers,” says Bieito. “They sing so well and come up with so many ideas. I always say directing is like playing tennis. I send the ball to their court and they play it back. I have great artistic faith in them. And it’s a delight to be able to work with a conductor who is specialised in this music.”

“I think one of Calixto’s qualities is that he makes everyone feel so free,” says Auer. “You see it in the rehearsals: because they all sense that freedom, they develop a lot of ideas together with Calixto and they surpass themselves. That is quite special.” Bieito: “I never try to explain the character to the singer, because then I build a wall. I prefer to leave it open. We don’t know who we are in life until we have lived through certain situations. Similarly, we can only say ‘This is the character’ once we have been through situations with that character in rehearsals, which means right at the end.” This shows once again that Bieito is not the kind of director who has everything planned before he starts rehearsals. Rather, his productions evolve in the rehearsal room in partnership with his singers. His Giulio Cesare is not finished until the premiere, the moment when all the elements come together. He does not lecture audiences either, preferring to leave things undefined to a certain degree. He offers audiences visual imagery that resonates at a deeper level and lets them interpret it, each in their own way.

Text: Jasmijn van Wijnen

Translation: Clare Wilkinson

Programmaboek

Become a Friend of Dutch National Opera

Friends of Dutch National Opera support the singers and creators of our company. That friendship is indispensable to them and we are happy to do something in return. For Opera Friends, we organise exclusive activities behind the scenes and online. You will receive our Friends magazine, have priority in ticket sales and a 10% discount in the Dutch National Opera & Ballet shop.