We Are The Lucky Ones

Performance information

Voorstellingsinformatie

Performance information

We Are The Lucky Ones

Philip Venables (1979)

World premiere

Duration

1 hour and 40 minutes

This performance is sung in English, with surtitles in Dutch and English. The surtitles are translated by Eveline Karssen.

A Song and Dance of Love and Death

Libretto Nina Segal en Ted Huffman

World premiere

14 March 2025

Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam

Musical direction

Bassem Akiki

Stage direction and set design

Ted Huffman

Costume design

Ted Huffman

Sonoko Kamimura

Lighting design

Bertrand Couderc

Video design

Nadja Sofie Eller

Tobias Staab

Movement

Pim Veulings

Dramaturgy

Nina Segal

Laura Roling

One

Claron McFadden

Two

Jacquelyn Stucker

Three

Nina van Essen

Four

Helena Rasker

Five

Miles Mykkanen

Six

Frederick Ballentine

Seven

Germán Olvera

Eight

Alex Rosen

Orchestra

Residentie Orkest

Interviewers

Mélie Boltz Nasr (France and Switzerland)

Yasmin Hafesji (United Kingdom)

Jessica Latowicki (United Kingdom and USA)

Margriet Prinssen (The Netherlands and Belgium)

Johann-Heinrich Rabe (Germany and Austria)

Nina Tind Jensen (Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Faroe Islands and Iceland)

Co-production with Ruhrtriennale

Production team

Assistant conductor

Lochlan Brown

Assistant directors

Sonoko Kamimura

Masha Zhukova

Evening direction

Masha Zhukova

Assistant set design

Bart van Merode

Repetitors

Jan-Paul Grijpink

Charlie Bo Meijering

Language coach

Alexander Oliver

Stage managers

Roland Lammers van Toorenburg

Emma Eberlijn

Sanne van Loenen

Artistic planning

Emma Becker

Master Carpenter

Jeroen Jaspers

Lighting manager

Coen van der Hoeven

Props crewmen

Niko Groot

Set supervision

Sieger Kotterer

Costume supervision

Claire Nicolas

Senior dresser

Jenny Henge

Senior make-up artist

Frauke Bockhorn

Sound engineer

Juan Verdaguer

Surtitles director

Eveline Karssen

Surtitles operator

Maxim Paulissen

Senior music librarian

Rudolf Weges

Production manager

Emiel Rietvelt

Orchestra inspector

Harm Jan Schwantje

Based on interviews with

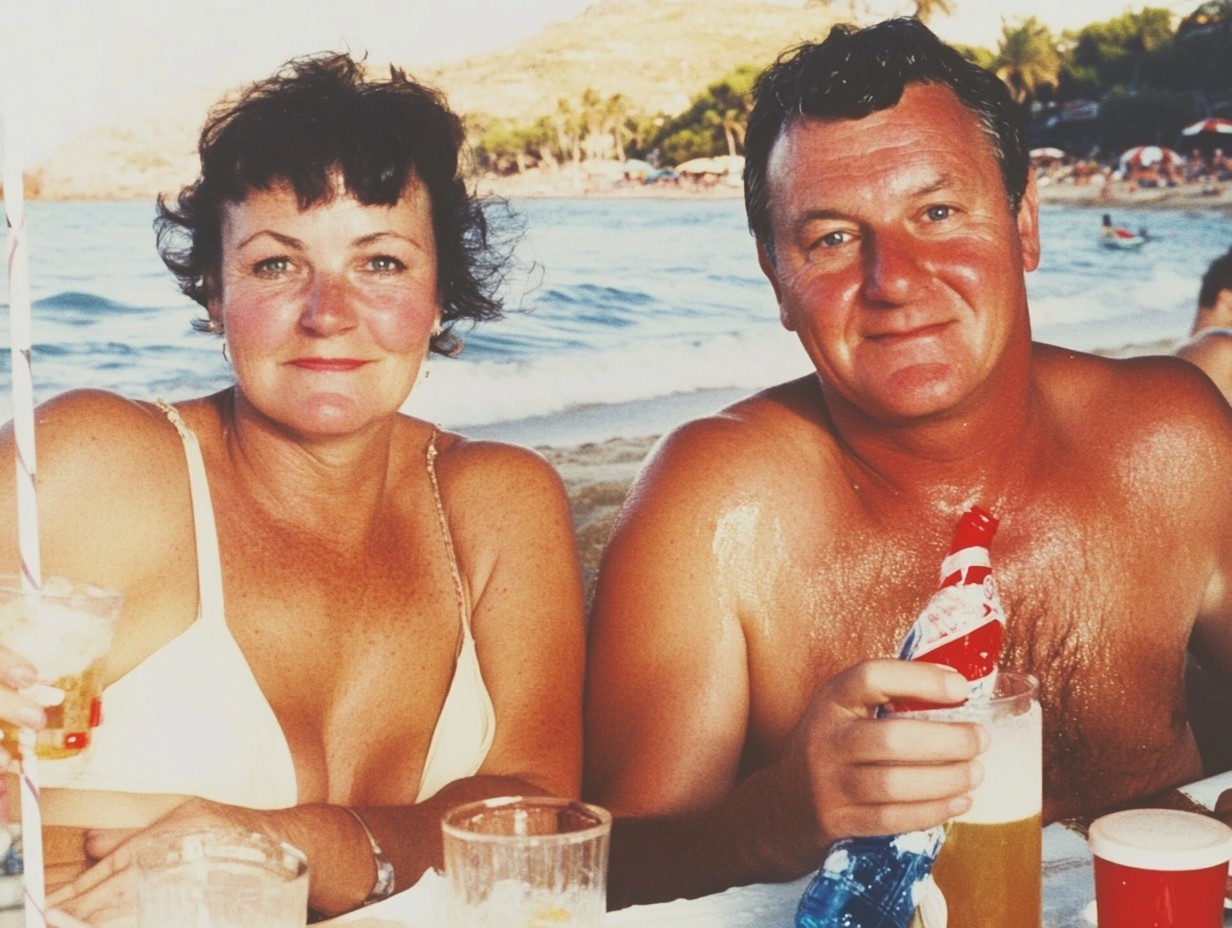

Jytte Aarsland, Stanley Nelson Adams, Annet Bakker, Michel Chapuis, Bernard Dumail, Görel Elf, Jan Erik Eriksson, Christian Gomard, Wil Hallers, Gun Hiselius, Marjolijn van der Hoeven-Heijink, Frits van der Hoeven, Trynke Hofman, Morten Johannesen, Hansje Kalt, Ineke Kokernoot, Tilmann Krämer, Friedemann Küppers, Ahmed Laboudi, Jos Lams, Samuel de Leeuw, Josiane Madron, Monique Mangado, Denis Mangado, Frank Maszro, Vera Matschke, Wenche Medbøe, Elisabeth Panknin, Hanna Lore Petzenberger, Mieke van der Pol, Felizitas Ringham, Eva Rowley, Han Singels, Karin Steinke-Hansen, Dietrich Stiller, Jean-Louis Vaysse, Hans van ‘t Veer, Christine Venables, Geoff Venables, Arnes Verden, Jan de Vries, Jean Waldman, Helen Wijngaarde, Tineke de Wit, Gunter Wolf, Ies Zwaaf, Riek Zwaaf-Deen en vele anderen die anoniem wensten te blijven.

Residentie Orkest

First violin

Pieter van Loenen

Emi Ohi Resnick

Naomi Bach

Orges Caku

Yuki Hayakashi

Myrte van Westerop

Irene Piazza

Francisca Portugal

Pieter Verschuijl

Hester van der Vlugt

Second violin

Justyna Briefjes

Remus Rimbu

Barbara Krimmel

Ben Legebeke

Abel Rodriguez Garcia

Sergiy Starzhynskiy

Cato Went

Sandra van Eggelen Karres

Viola

Hannah Strijbos

Moira Bette

Jan Buizer

Elisabeth Runge

Tanja Trede

Jozefien Dumortier

Cello

Roger Regter

Iedje van Wees

Justa de Jong

Miriam Kirby

Tom van Lent

Jean Baptiste Schwebel

Double bass

Frank Dolman

Jorge Hernández

Astrid Schrijner

Jos Tieman

Flute

Martine van der Loo

Janneke Groesz

Obo

Roger Cramers

Clarinet

Hans Colbers

Jasper Grijpink

Alfonso Saiz Revuelta

Bassoon

Dorian Cooke

Erik Reinders

Saxophone

Daan van Koppen

Deborah Witteveen

Horn

Rene Pagen

Elizabeth Chell

Mirjam Steinmann

Christian Fisalli

Trumpet

Erwin ter Bogt

Robert-Jan Hoffman

Trombone

Timothy Dowling

Arno Schipdam

Wouter Iseger

Tuba

Elias Gustafsson

Timpani

Martin Ansink

Chris Leenders

Gerda Tuinstra

Joeke Hoekstra

Georgi Tsenov

Harp

Mathilde Wauters

Piano

Sepp Grotenhuis

Accordeon

Robbrecht van Cauwenbergh

In a nutshell

About the world in change, the voices of a generation and the dance rhythms of composer Philip Venables, among other things.

In a nutshell

World of change

World of change Life in Western Europe has changed almost beyond recognition during the lives of the generation at the heart of this opera. The interviewees were born during or shortly after the Second World War, when Europe was in ruins and even basic necessities were in short supply. This was followed by a period of rapid economic growth, the construction of the modern welfare state, incredible technological advances, the formation of the European Union, globalisation and a change in social structures. Social inequality within Western Europe decreased during their lifetimes, to an extent their parents’ generation could hardly have imagined. This generation was exceptionally “lucky”, as one of the interviewees put it, in numerous ways.

Based on interviews

We Are The Lucky Ones is based on interviews with people born in the 1940s. Six researchers spoke with around 80 interviewees from the Netherlands, Belgium, the United Kingdom, France, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, the Faroe Islands, Iceland and the United States. In response to set questions, they talked about their work, important purchases, the people they loved, their travels and what they thought the future held. These conversations resulted in around 350 pages documenting their memories, thoughts and reflections. The director and writer Ted Huffman, writer Nina Segal and composer Philip Venables studied this material in search of common threads, overarching themes and striking experiences. This became the basis for their libretto for We Are The Lucky Ones.

Voices of a generation

We Are The Lucky Ones was written for a symphonic orchestra and a cast of eight soloists. Rather than portraying specific characters in the traditional sense, the singers come on stage together to jointly bring the many voices of a single generation to life. They function as vibrant narrators, vividly embodying a wide range of people and experiences in brief snatches. Then they break the illusion — repeatedly, after each scene (of which the opera has 64). The audience is guided by the passage of time: the opera starts with memories of events in the 1940s and continues through to the present day.

A Song and Dance of Life and Death

The opera includes a lot of dance music, for example in the ‘interludes’ marking festive moments such as the liberation from German occupation or the start of the new millennium. In both solo and ensemble scenes, Venables frequently incorporates a wide variety of dance rhythms. For instance, one of the performers sings a tango about her cleaning lady, while the entire ensemble sings how lucky they are in a whirling 3/4 time. Venables’ signature eclectic style is enriched in We Are The Lucky Ones with influences from classic Hollywood film music, big band and swing. As a result, his orchestration gives a prominent role to the brass section and percussionists.

The story

We Are The Lucky Ones tells the story of a generation. It is based on interviews with around 80 people in Western Europe who were born between 1940 and 1949.

The story

We Are The Lucky Ones tells the story of a generation. It is based on interviews with around 80 people in Western Europe who were born between 1940 and 1949. Their memories form a collective time capsule of the past eighty years, told as one continuous life story in music theatre form. Following individual experiences and societal changes over the decades, the opera raises crucial questions about the relationship between the private and the political, the impact of our choices and what truly matters in the end.

Scene overview

Prelude

1. Born in a Snowstorm 2. House is Gone 3. Shoes 4. House on Fire

5.Train 6. The Soldier

7. Interlude 1: End of War (a dance)

8. Orange 9. Real Mother 10. Ration Card 11. First Kiss 12. Back Yard

13. School Test

14. Interview 1 (spoken)

15. First Holiday 16. Father’s Music 17. School Exchange 18. Dance

19. Interlude 2: Youth (a dance)

20. Shot Him 21. Lectures 22. Getting High 23. First Job 24. Bombs 25. Freedom 26. Rocket 27. Marry Me?

28. Interlude 3: Wedding Party (a dance)

29. Interview 2 (spoken)

30. Baby 31. New House 32. The Hunter 33. Promotion 34. My Daughter

35. Interlude 4: Birthday Party (a dance)

36. Wall Falls 37. America 38. Someone Else 39. Work

40. Interview 3 (spoken)

41. House Is Quiet

42. Interlude 5: Millenium Party (a dance)

43. Plane 44. Flying is Cheap

45. Interview 4 (spoken)

46. Giving 47. Reunion 48. Computers 49. We’re Lucky 50. Cleaning Lady

51. Interview 5 (spoken)

52. Money 53. Miss the Step 54. Grandsons

55. Interview 6 (spoken)

56. Terror 57. Dead Dog 58. Fuck You 59. It’s Quiet

60. Interview 7 (spoken)

61. Lucky Ones 62. It’s Snowing

63. Interview 8 (spoken)

64. Regrets

Epilogue

Timeline

A brief summary of events and developments that have affected life in Western Europe over the past eighty years — and therefore the lives of the generation at the heart of We Are The Lucky Ones.

Timeline: Western Europe since 1940

A brief summary of events and developments that have affected life in Western Europe over the past eighty years — and therefore the lives of the generation at the heart of We Are The Lucky Ones.

1945

On 8 May 1945, Nazi Germany capitulates to the Allied Forces, thereby ending the Second World War in continental Europe. A new division of power emerges soon afterwards. To the west of the Iron Curtain lies capitalist, ‘free’ Europe and to the east are the countries in the sphere of influence of the communist Soviet Union. Germany is torn apart as a result, divided from 1949 onwards into West Germany — the Federal Republic of Germany — and East Germany — the German Democratic Republic.

1947

The welfare state takes shape in various European countries. In the Netherlands, the foundations are laid in 1947 with the emergency provisions for the elderly (the predecessor of the General Old Age Pensions Act).

1951

In 1951, six European countries (Belgium, West Germany, France, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) sign the Treaty of Paris, establishing the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). The idea was that joint control of the coal and steel industries would prevent individual countries from developing armaments and using them against one another.

1957

The six ECSC countries sign the Treaty of Rome, extending their cooperation into other economic sectors. The European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) are founded.

1961

The communist government in East Germany builds a wall through Berlin. The Berlin Wall becomes a symbol of the division between Eastern and Western Europe during the Cold War.

1962

The introduction of the contraceptive pill makes it easier for women to go to university and get jobs.

1968

A revolt by students and workers in France threatens the very foundations of the state. Student protests spread through other European countries too.

1971

When the findings of the report Limits to Growth by the Club of Rome are leaked, they cause worldwide commotion. “If everything and everyone carries on the same way they do now”, writes Dutch newspaper NRC on 31 August 1971, “there will be a massive catastrophe within a few decades. The only question is whether the catastrophe will be caused by hunger, depletion of essential raw materials or the pollution of the Earth.”

1973

After the Yom Kippur War of October 1973, oil-producing countries in the Middle East enforce huge price rises and restrict sales to certain European countries. That leads to economic problems throughout the EEC.

1989

The Berlin Wall falls, opening up the border between East and West for the first time in twenty-eight years. In October 1990, Germany is reunited after more than forty years, with the former East Germany becoming part of the European Community.

1992

The Maastricht Treaty establishing the European Union is signed on 7 February 1992 by all twelve members of the European Community.

1993

The internet is opened up for use by companies and private individuals. It takes a few more years before the internet becomes so embedded that we now cannot imagine life without it.

1995

The Schengen Agreement comes into force in seven countries: Belgium, Germany, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. It makes travel between these countries possible without passport controls at the borders.

2001

Hijacked planes crash into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York and into the Pentagon in Washington. Nearly 3,000 people are killed.

2002

The euro is introduced as the official currency in twelve of the then fifteen EU member states.

2007

Apple presents the iPhone, marking the start of our modern-day smartphones.

2008

The world economy is rocked by a major financial crisis. The problems start with mortgage loans in the United States but threaten various European banks as well.

2015

In 2015, 1.3 million people request asylum in Europe, the highest number in one year since the Second World War. The increase is mainly due to the war in Syria. After a week in which several hundred refugees crossing the Mediterranean in boats drown, the situation is labelled a refugee crisis.

2016

In a referendum, 52 per cent of voters in the United Kingdom vote in favour of Brexit, for the UK to leave the European Union after more than forty years as a member state. Brexit takes effect on 31 January 2020.

2020

The coronavirus pandemic becomes a severe public health emergency.

2022

In the early morning of 24 February 2022, Russian troops invade Ukraine from the east and from Crimea and Belarus.

2025

Geopolitical relations between the United States and Europe are tense. At the international Munich Security Conference, the US Vice President J.D. Vance attacks Europe, accusing its states of abandoning democratic values by keeping far-right parties out of government and restricting the freedom of speech.

The story of a generation

In We Are The Lucky Ones, the composer Philip Venables, director Ted Huffman and librettist Nina Segal embarked on a unique music theatre project. In this opera, they tell the story of a generation born in the 1940s: a generation whose lives are inextricably linked with the developments in Western Europe.

The story of a generation

In We Are The Lucky Ones, the composer Philip Venables, director Ted Huffman and librettist Nina Segal embarked on a unique music theatre project. In this opera, they tell the story of a generation born in the 1940s: a generation whose lives are inextricably linked with the developments in Western Europe.

The artistic team found inspiration in the work of the writers Annie Ernaux and Karl Ove Knausgård. The French author Annie Ernaux wrote The Years (2008), an ‘autosociobiography’ of the period 1941-2006. In this book, she chose a form that let her both report on a changing world and describe her own position in that process. Ernaux plays a sophisticated game with subjectivity and objectivity, the interaction between personal and collective experiences.

Another key point of reference was My Struggle, the series of six autobiographical volumes by the Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgård. He gives a candid, no-holds-barred account of his life and his family history, down to the smallest detail. “What fascinated us about The Years and My Struggle,” says director and co-librettist Ted Huffman, “is how both authors give a picture of an era and explore it through the lens of their personal experiences. Their books succeed magnificently in combining the personal and the political.”

Grand scale

The artistic team grew fascinated by the generation portrayed by Ernaux in her novel. “These were people born during or shortly after the Second World War,” says Huffman. “They grew up during the period of reconstruction, at a time of great scarcity. Much of Europe was in ruins. What this generation experienced during their lifetimes is unprecedented in the history of humankind: explosive economic growth, the creation of the welfare state, radical technological changes, increasing globalisation and changing social relations.”

“What appealed to me was the scale and the apparent impossibility of this project,” says the librettist Nina Segal, who is collaborating with Huffman and Venables for the first time. “Knausgård told the story of just a single life and it took him six doorstop novels. In her novel, Annie Ernaux repeatedly zoomed in on one character and restricted herself to the French context. But Ted and Philip wanted to capture the lives of a whole European generation in a single opera. How do you condense the grand scope of something so extensive into a form that is compact but still meaningful?”

Interviews

Rather than creating a libretto from their own imaginations, the team based the texts on interviews with people born in the 1940s. “As a team, we share a deep interest in how people remember things and how they talk about the past,” explains Venables. “In Denis & Katya (2019), one of the previous operas I created with Ted, we delved into the true story of two Russian teenagers who ran away from home and were ultimately killed in a fatal shoot-out with the police. We spoke to classmates and journalists, read media reports and incorporated quotes from these sources in the opera’s libretto.”

The team used a similar approach for We Are The Lucky Ones, but on a much larger scale. Six researchers interviewed dozens of people from the Netherlands, Belgium, the United Kingdom, France, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, the Faroe Islands and Iceland, as well as a few from the US. Some of them had migrated to or from Europe at some point in their lives while others had spent their entire lives on the continent. In response to set questions, the interviewees talked about their work, key purchases, lovers, their travels, their regrets and what they thought the future held. The artistic team was given transcripts and translations of the interviews.

They ended up with a huge pile of some 350 A4 pages of source material to work through. The team studied the interviews closely, looking for recurring elements and core themes. They also noted interesting phrasing and word choices. That gave them the bare bones of the libretto. “We wanted to focus on what is normally considered neutral or ordinary,” says Huffman. “So we left out stories such as a knife fight on a beach in Vietnam, which was told as a dramatic anecdote in one of the interviews. We were looking more for the general trends than the exceptions.”

Middle class

That focus makes We Are The Lucky Ones largely the story of the middle class and how it has changed. Venables: “In this opera, we look at the ‘winners’, the people who benefited most from the post-war economic expansion. And the increasing prosperity after the war also meant more and more people joined the middle class.”

Within the middle class, there was a shift in the mindset over time. “After the war, there was a shared sense of needing one another to rebuild,” says Huffman. “That idea feels so distant from the individualism and neoliberalism that dominate today.”

Venables stresses that We Are The Lucky Ones is not criticising that generation. “These people were out on the streets fighting for the very rights and protections that are now being dismantled. They’re often dismissed as ‘boomers’, but the people we spoke to are not remotely ignorant of today’s issues. Many are politically engaged and highly aware of the political landscape.”

Spirits

We Are The Lucky Ones is an opera for eight singers, whose roles are simply numbered One to Eight. The performers don’t play individual characters; they function as mouthpieces for their generation, infused with various voices. It is as if the spirits of the interviewees briefly take hold of them.

The presence of ‘spirits’ is also suggested subtly by the minimalist scenography in which a ‘ghost light’ plays a prominent role. Older theatres, especially in the United States, have a tradition of leaving one bulb lit on the stage at night when the theatre is empty. That is not only for safety reasons but also out of a superstitious belief that the ghosts of the theatre need to be appeased.

Performer and text

The team also plays deliberately with unexpected combinations of performer and text. One striking example is the tenor who briefly embodies an East German single mother. “It wasn’t about finding the ‘right’ or most obvious performer to match a particular text,” explains Segal. “Quite the opposite. Creating this clash is how we emphasise that the story we’re telling transcends the particular and the individual.”

In addition to the solos, the opera contains scenes that centre on a dynamic form of collective storytelling. A good example is the scene in which a tenor sings about eating an orange for the first time. While he recalls this memory, the entire ensemble sing in unison to represent the voice of the mother explaining to the child how to peel an orange. Another telling example is the quadrupling of voices in a proposal scene: the woman who is being asked to marry the man is played by all four female singers.

Chronology

In a collage of multiple voices and characters, the opera’s chronological structure — from the 1940s to the present day — anchors the audience. “We’re presenting this archetypal journey,” says Venables. “You fall in love, get a job, get married, buy a house, have kids, maybe a second car, a bigger house, retire, spend time with the grandkids. We want people to see themselves and others in that structure.”

“That progression through life provides a structure and lets us address bigger themes,” adds Segal. “While the performers in the opera are singing cheerfully about buying a house, the audience knows these are opportunities younger generations can no longer assume they will have. In this way, major issues like the climate crisis, political instability and inequality are subtly present in the opera. But we root it in the personal — people weren’t having children or buying second cars with the intention of harming the planet. They were making choices that felt meaningful to them at the time.”

We Are The Lucky Ones uses two approaches for distinguishing memories. “On the one hand are the scenes where moments from the past are relived,” explains Venables. “We show life as it’s being lived — as dramatised or retold memories. Then there are scenes where people look back and reassess past decisions. That creates an interesting tension between past and present, between closeness and distance.”

Bigband and swing

For his composition, Venables drew on the kind of music this generation was listening to in their youth. “The dramatised memories are like little character studies, and I needed to find distinct musical forms for them — ones that provide some distance but also inject energy and life. That led to a variety of dance forms, rhythm and movement. I found myself almost unintentionally drawing on genres from the 1940s and ’50s — old Hollywood film music, big band and swing. That music carries a sense of romance, optimism and nostalgia.”

“Of course,” continues Venables, “the music is eclectic — there’s contemporary classical music as well. I wanted to evoke the feeling of a flowing river of memory.”

Imagination

A key term in Huffman’s stage direction is ‘imagination’. “The interaction between performers and audience is central to theatre, and we are going back to that essence. Rather than illustrating everything literally, we engage the audience’s imagination through music, text and dance.” Contrasts play an important role, says Huffman. “The audience sees eight people come onto the stage in elegant evening wear. That creates an immediate contrast between the past and the present when they start singing about childhood hardships.”

“Since dance and movement are so central to the piece,” continues Huffman, “we didn’t feel the need for an elaborate set. We mainly needed a space for storytelling. We also developed a visual language using projected photos and videos. This was the first generation to have their own cameras. And representation of the self has shifted dramatically over the past eighty years.”

“The way photography evolved mirrors larger social shifts,” adds Segal. “At first, photography was something rare that you only did on special occasions as you needed to have rolls of film and because of the cost and effort of getting them developed. But with the introduction of digital cameras and now smartphones, photography is everywhere. Nowadays however, in the AI era, photos and videos are increasingly unreliable.

Authentic artificiality

The photos and videos projected during the performance reflect that evolution. Video designers Nadja Sophie Eller and Tobias Staab trained an algorithm on real historical photos and videos. Then they used the algorithm to generate new photos and videos. The result is images that seem authentic at first glance but also have something uncanny about them.

Just as the writers Huffman and Segal created a partly fictionalised text based on real interviews, so Staab and Eller have built something fictional derived from authentic images. Like Denis & Katya, in a way We Are The Lucky Ones explores the grey area between truth and fiction. Will the people who shared their memories be able to recognise themselves in the opera? “Perhaps. Perhaps not,” concludes Huffman. “That’s the big question.”

Dutch text: Laura Roling

A portrait of the composer Philip Venables

We Are The Lucky Ones is the fourth opera by the British composer Philip Venables and his biggest venture so far. In his years collaborating with the director and author Ted Huffman, he has built up a reputation as an innovator who pushes the envelope of the operatic form.

A portrait of the composer Philip Venables

New connections between text and music

We Are The Lucky Ones is the fourth opera by the British composer Philip Venables and his biggest venture so far. In his years collaborating with the director and author Ted Huffman, he has built up a reputation as an innovator who pushes the envelope of the operatic form.

Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century operas were constantly adapting to the theatrical styles of their day, from the courtly dramas and comedies of the eighteenth century to the Schillerian dramas of the nineteenth century and the verismo potboilers of the early twentieth century.

Then the art form got stuck in a rut. Many new operas today adapt middlebrow novels or movies in clumsy attempts to draw audiences with a title they’ve heard of. If you want opera to be living theatre, it can be frustrating to see how often this art form remains lifeless. That is why critics and audiences have greeted the theatrical collaborations between Venables and Ted Huffman with such praise and enthusiasm. Unburdened by convention, these works — each very much in its own way — have taken music theatre back to first principles. “My main aim with opera is finding different syntheses, different interactions between music and text,” Venables explains.

Music education

Perhaps this eagerness to examine things afresh arose from his atypical entry into the too-often rarefied world of art music. Venables, who grew up in Chester in the north of England, began playing the violin at age nine thanks to the primary school music service. “I happened to be given a violin,” he says. “Other children got a flute or a clarinet. Then I attended a state secondary school that happened to have a really good music department.” He began composing on the violin, exploring the possibilities of the instrument outside the pieces he was learning for his lessons.

That music department provided a “safe space during break and lunchtime, away from the violence of the school playground.” Sadly, the kind of music education that enabled Venables’ career has been slashed to the bone in the name of austerity. “My parents contributed towards the music lessons,” he says, “but everything else was funded by the schools. If it wasn’t for that music service when I was nine, I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing now. The field is so driven by inherited wealth and tradition that these public services are the only way most people get access to the music.”

As a student — and still today — the composers about whom Venables is most passionate are not the ones you might expect to be cited by a contemporary composer: he loves Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev, Shostakovich and Stravinsky. “The big Russian music of the turn of the century,” Venables says. “Bombastic. Heart on sleeve. I still see so much connection with that music in my own taste. I always love big gestures and cinematic storytelling.”

Spoken text

Venables’ interest in the marriage of music and text came not through traditional text settings in song or music theatre but through work with spoken text. In 2015, he received an invitation from the London Sinfonietta to contribute to a concert on the evening of the UK general election. That led to Illusions, a collaboration with the British underground drag artist David Hoyle. Other composers came up with what Venables calls “woolly messages about love and hope and happiness after all those years of cuts”. In contrast, Venables’ Illusions started with video footage of Hoyle ranting drunkenly, in the style of his inimitable stage shows, about elections, democracy and austerity. These clips were then cut, spliced and integrated into a broader musical structure. “It was simultaneously angry and joyous,” he says. The work was expanded further in 2017.

This approach to setting text to music was influenced less by traditions of composed music and more by the internet culture and electronic dance music, about both of which Venables is passionate. As inspirations, he cites the track ‘Since I Left You’ by The Avalanches, and the YouTube artist Cassetteboy, whose absurdist mashups of politicians’ speeches create melodies from their words.

Sarah Kane

His first opera, 4.48 Psychosis, is an adaptation of the Sarah Kane play of the same name. Conventional plays, where characters speak to one another in realistic dialogue, have only a single register of text. Kane’s play, an exploration of mental illness that veers between monologue, dialogue, poetry, prose and lists, is different. “I found it prosodically and compositionally exciting because you can find different musical treatments for each kind of text,” Venables says.

4.48 Psychosis was also when Venables began working with Ted Huffman, although the native New Yorker had met Venables years before. Their first work together was, Venables modestly says, “a success”. This is an understatement: the opera received rave reviews in the global press and was performed at a variety of opera houses and festivals.

“Fired up by the success of 4.48 Psychosis, we entered a very fertile period,” Venables says. Both Huffman and Venables were hungry for projects that did not take the dictums of opera for granted. The pair soon settled on two subjects for new music theatre collaborations: one a classic gay-liberation era fable, the other a news article about two teenagers in Russia who, heavily armed and barricaded in a dacha, live-streamed their confrontation with the Russian Special Forces.

Theatrical storytelling

The two very different stories led to very different works, but both put explorations of theatrical storytelling at the centre of their formal logic. In Denis & Katya, which premiered at Opera Philadelphia in 2019 (and was performed at Dutch National Opera in 2022), two singers narrate the reconstructed story through interviews with people who had known the teenagers or witnessed the events, news articles, text from the livestream itself — including comments posted by viewers — and messages between the composer and librettist as they discussed the project. Each type of text offers different opportunities for prosody and musical effect. The music itself — for singers, electronics and four cellos — is difficult to characterise, not in terms of harmony or musical style, but in the way that musical form seems to emerge naturally from speech; the operas of Janacek form an interesting point of comparison.

In The Faggots and their Friends Between Revolutions (2023), meanwhile, a group of performers come together to enact a gay liberation fable. Cast with multitalented performers rather than opera singers, the music is scored for the instruments its cast can play, in a pastiche of very diverse musical styles. The work is created onstage anew every night, collectively, without a conductor; a metonym for the kinds of queer community it describes.

Performers and characters

“One thing we’ve been trying in our work is to break the one-to-one link between performer and character,” Venables explains. In 4.48 Psychosis, various performers portray a single character whereas in Denis & Katya, two performers portray multiple characters. In The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions, the performers are simply themselves: storytellers.

This approach to storytelling is continued in Venables and Huffman’s latest collaboration, which emerged from their shared appreciation for the book The Years by Nobel Literature laureate Annie Erneaux. It is a collective memoir of a generation of post-war French children who grow richer and older, who rebel, become consumers, and either do or do not give up broader political fights for justice and collective liberation.

Working with the playwright Nina Segal, Venables and Huffman — and a team of six researchers — interviewed nearly eighty people born in the 1940s. One question for the artistic team was how much responsibility this generation bears for the current state of the world. But Venables thinks discussing the system is more interesting than blaming the individuals within it.

Arranged in the order of the generation’s collective lifespan from birth to old age, the score evokes the music styles that shaped the lives of this generation: big band and Hollywood music, jive, swing — music that has a sense of optimism or luxury. These sounds, shaping the river of memories, bring joy to the opera. It is music from a time when that generation had not yet lost its innocence. “The music brings the memories to life,” says Venables. “There are ghosts in the theatre.”

Text: Ben Miller