About Frieda Belinfante and how she was forgotten in the Netherlands

World War II resistance activist, first female conductor and much, much more

Tekst: Hein van Eekert

Frieda Belinfante was not one to hesitate: she jumped right in when she felt that a situation called for action. This multi-talented musician, icon, resistance activist and example to many will be celebrated in Frieda Belinfante, a one-woman musical, which will be performed at Studio Boekman as part of Theater na de Dam, the annual theatre manifestation in early May marking the Remembrance of the Dead in the Netherlands that honours those who died during the Second World War and subsequent conflicts.

In 1943, the third year of the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, a group of artists, including sculptor Willem Arondéus and cellist and conductor Frieda Belinfante, embarked upon an important and extremely dangerous mission. Until then, the members of their group had used their artistic skills and knowledge, as well as their intelligence and intrepid courage to forge personal documents to protect Jews from deportation. At some point, however, they realised that they had been compromised when a forgery was discovered: the serial numbers of the forged identity cards no longer corresponded to those in the population register. There was nothing for it. The population registry building needed to be bombed.

The group produced fake police uniforms and selected nine young men from their ranks to carry out the assault on the building. One of them was a doctor who injected the guards with morphine to immobilise them. They were carried to the garden. The attackers put a sign outside the burning building to warn passers-by of the risk of explosion. No one died in the attack. The occupying forces did not show any mercy. After the successful assault on the building, the conspirators were betrayed to the Nazi-run government, arrested and sentenced to death.

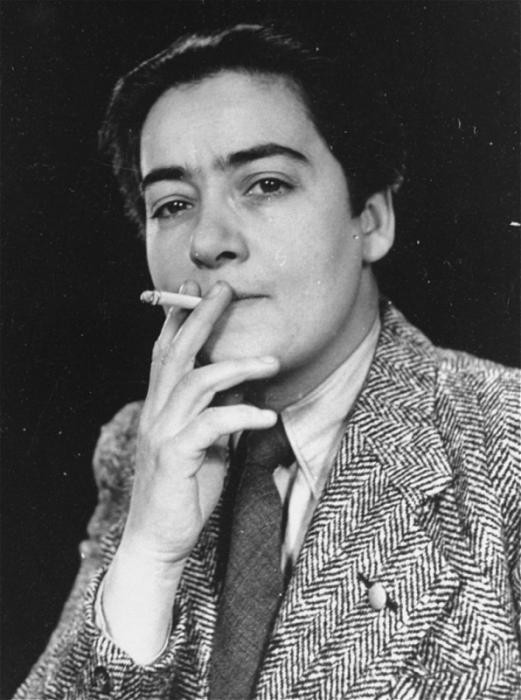

Frieda Belinfante

‘If you accept the first step because you feel there’s no harm in it, the second and third will follow, and before you know it, you’re complicit’

Forward-thinking

Frieda Belinfante, who was involved in all the preparations, did not participate in the actual assault. Her co-conspirators felt it was too dangerous for a woman. She was on the roof of a building when it happened and saw the glare of the fire. She was not happy that her accomplices did not let her take part in the assault, but she managed to escape arrest, although she was betrayed too. She disguised herself as a man. Successfully so. ‘I knew something was wrong, so I thought I’d better disappear. That’s why I wasn’t arrested. They knew where I lived, but I’d already left when they came to get me,’ Frieda explained later in a documentary. She was proactive and always thinking ahead. As early as when she studied conducting with Hermann Scherchen in Switzerland, she warned him of things to come in Europe. That was before the Germans even occupied the Netherlands.

On 24 April 1940, Frieda had different things on her mind: she conducted her ensemble Het Klein Orkest in the premiere of Leo Smit’s concerto for viola and strings. 10 May 1940, Frieda’s 36th birthday, is the day of the German invasion of the Netherlands. From then on, Belinfante would always harbour a bit of an aversion to 10 May. In the first few weeks after the capitulation (15 May 1940), some were trying to hold out hope that nothing much would change during the occupation and went about their business as usual. But Frieda disbanded her ensemble. For good reason: she did not want to be banned from playing Jewish music, nor did she want to have to let go of Jewish musicians. ‘If you accept the first step because you feel there’s no harm in it, the second and third will follow, and before you know it, you’re complicit.’

The last thing Frieda wanted to be was complicit. Being half-Jewish, she would have qualified for dispensation from the Dutch Chamber of Culture, which would have allowed her to continue to perform. But she did not bother to apply. She just stopped performing in 1942. It quickly dawned on her that, if the Jewish people in the Netherlands were forced to carry new identity cards, this would allow the Nazis to keep a close eye on them. They needed forged identity cards. She encouraged her friends and family to ‘lose’ their identity cards and apply for new ones. She used the ‘lost’ identity cards to make forgeries for Jews.

‘Frieda was multifaceted and extremely talented’

‘Frieda was a total go-getter,’ says Toni Bouman, author of the excellent biography Een schitterend vergeten leven: de eeuw van Frieda Belinfante (A beautiful forgotten life: the age of Frieda Belinfante). Bouman, who became a personal friend of Belinfante’s over the years, characterises her as a woman ‘who was ready to tackle whatever challenges and opportunities came her way, who had a broad and diverse range of interests and an inquisitive mind, and whose moral compass was spot-on.’ Belinfante had a sense of humour and she was charismatic. Even as a child, her sister Renée said, she was loved by boys and girls alike. ‘Frieda was multifaceted and extremely talented,’ as Toni Bouman puts it.

Frieda Belinfante was definitely multi-talented: she was a leading musician and one of the first Dutch female conductors. But she was also a resistance activist, a great teacher, she made delicious jams, and she was a master forger. And she was a member of the LHBTQ+ community, which was being persecuted during the war. Anyone who delves into her life will see that she was authentic. Unlike many social media influencers today, she was not trying to be someone else or portray an image. She knew who she was: her true self. She tried to act, help, save people, study, create, teach, play music and lead where she could. And when there were no opportunities in the Netherlands for her to do that, she left the country, only to be forgotten by it. In the United States, where she ended up living, she did not share much about her past.

Toni Bouman, biograaf

‘She was a woman who was ready to tackle whatever challenges and opportunities came her way, [...] and whose moral compass was spot-on’

The Belinfante family

Frieda Belinfante was born in the heart of Amsterdam; she was the third girl in the family. She had two older sisters: Dolly and Renée. Dolly died at a young age due to complications from appendicitis. Her parents had hoped for a boy, but he did not come into the world until after Frieda. His name was Bob. He and his wife committed suicide at the start of the war. ‘I was a bit rough-and-tumble, but I wasn’t a boy.’ Frieda’s father was Ary (Aron) Belinfante, who was the leader of a music school and a concert pianist. He was of Jewish descent. The children were given musical training: Dolly played violin, Renée played piano and Frieda played cello. ‘My father looked at our hands,’ Renée explained later, ‘but he didn’t look all that well, because Frieda had much smaller hands than I did. To play cello, you need giant paws. Frie always struggled with that instrument.’

Rude career interruption

Frieda found work as a cellist at Haarlemsche Orkest Vereeniging – conducted by Eduard van Beinum – and joined Het Amsterdamsch Trio. The other two members of this trio were composer Henriëtte Bosmans and flautist Johan Feltkamp. Frieda lived with Bosmans as her partner for some time in the 1920s and was married to Feltkamp for a few years in the 1930s. ‘Henriëtte Bosmans was a lonely person. She took more than she gave,’ Belinfante explained, ‘but I didn’t mind, because I had an abundance of admiration to offer.’

Although Bosmans wrote a cello concerto for her, Frieda realised that she would never make it big as a cellist. She started conducting the Sweelinck Orchestra of the University of Amsterdam and discovered that conducting was her great passion. She took a course with Herman Scherchen in Switzerland to perfect her conducting skills. In recognition of her abilities, she was awarded a prize: a debut engagement with the famous Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. Unfortunately, she would never get to claim her prize because the war had started. When she was forced to go into hiding after the attack on the population register, she ended up in a refugee camp in Switzerland. Her former teacher Scherchen saved her from being sent back. She settled in Winterthur.

Return to the Netherlands

Life for Frieda must have been extremely hard after her repatriation: family members had died, friends were gone for ever. Her return to the Netherlands was an utter disappointment. While she was touted as an exceptionally promising conductor in the Netherlands before the war, she struggled to find work after the war had ended. Artists who had collaborated with the occupying forces during the war mostly just went on working after 1945. ‘No one talked about the past. Everyone was doing their own thing, trying to make money. We thought everything would be better, but nothing had changed. I just couldn’t enjoy my work any more.’ Frieda Belinfante left the Netherlands in 1947. She first went to New York and then travelled all over the United States: ‘It felt like a new beginning. No one there knew what the Netherlands had been through during the war.’

Hollywood

A new career, the love of her life, happiness: that is what Frieda found on the West Coast of the United States. She conducted an orchestral ensemble of Hollywood studio musicians who were craving to play the scores of the great composers. She was the first woman in the world to be appointed resident conductor of a philharmonic. She taught and had a great impact on the people around her. She became a success story, which is why it is shocking that – despite a number of documentaries about her and an excellent biography – Frieda Belinfante, who died in 1995, was so easily forgotten in the Netherlands as a resistance activist and a conductor.

Frieda Belinfante : One Woman Musical

In 2022, writer Sietse Remmers, composer Frank Irving, director Sytske van der Ster, and actress and singer Esther Lindenbergh developed a first version of a musical theatre performance about Frieda Belinfante. Dutch National Opera decided to present a long-form version with live musical accompaniment, as part of the Theater Na de Dam programme. Composer Leonard Evers created expansive compositions and took on the opera’s musical coordination. In Frieda Belinfante, Lindenbergh takes the audience on a journey through Frieda’s life, accompanied by the Chekhov Trio. Over the course of 75 minutes, we catch a glimpse of her childhood years in Amsterdam, her sexual awakening, the wartime years, her subsequent depression, and her new life in the United States, where she carved out a successful career as a conductor and met the love of her life.

-

Frieda Belinfante will be performed in Studio Boekman at Dutch National Opera & Ballet on 4, 5, 8 and 9 May. For more information and tickets, please visit www.operaballet.nl.