Giselle

Preface

Voorwoord

Preface

An enchanting classic

Timeless, legendary and a global favourite. Giselle is one of the oldest classical ballets in the world and among those that are still danced most often today. It occupies a special place in many people’s hearts – mine included. Giselle was the first ballet I ever saw, performed back then by the famous Dutch dancers couple Alexandra Radius and Han Ebbelaar in the leading roles of Giselle and Count Albrecht. Their pas de deux in the iconic second act was magical and something I’ll never forget it. That was the evening my love of classical ballet was kindled.

Fourteen years ago, Rachel Beaujean and Ricardo Bustamante created a new version of Giselle for Dutch National Ballet. With great care and attention, they revitalised the ballet and added new elements to it, while remaining true to the original. They thus succeeded in creating a production that’s still poignant today – which is exactly what you must aim for if you want to pass on heritage to a new generation. Moreover, in my view this Giselle is also one of the most beautiful versions with regard to design, thanks to the wonderful sets and costumes by Toer van Schayk, who based his designs on eighteenth-century etchings and pen drawings.

In recent years, our company has had the pleasure of dancing the production by Rachel and Ricardo to full houses in the Netherlands and far further afield: from China to Colombia, and from Sweden to Turkey. I’m now looking forward to seeing our Giselle back on our own stage in Amsterdam in the coming period. Then in November, we’ll be taking the ballet to other theatres across the Netherlands as well. And in January, a new exciting Giselle project awaits us. From then on, a recording of the performance will be screened in cinemas all over the world!

But that’s still to come. First, various principal dancers will be making their debut as Giselle or Count Albrecht this month, and others are returning to the roles with new ideas and more experience of life. So one of the things we can look forward to in this performance series of Giselle is all the different interpretations of the dancers in the leading roles.

I hope that you, too, will be enchanted by Giselle – whether for the first time or as a seasoned spectator. Have a wonderful performance.

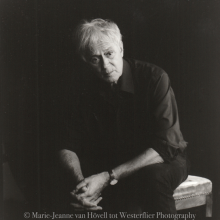

Ted Brandsen

Director Dutch National Ballet

Credits

Voorstellingsinformatie

Credits

Choreography

Marius Petipa, after Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot

Production and additional choreography

Rachel Beaujean and Ricardo Bustamante

Music

Adolphe Adam – Giselle, ou les Wilis (1841)

Costume and set design

Toer van Schayk

Lighting design

James F. Ingalls

Ballet masters

Guillaume Graffin

Sandrine Leroy

Larissa Lezhnina

Judy Maelor Thomas

Jozef Varga

Musical accompaniment

Dutch Ballet Orchestra conducted by Ermanno Florio

With cooperation of

The students and pupils of the Dutch National Ballet Academy

Rehearsal teacher pupils of the Dutch National Ballet Academy

Marieke van der Heijden

World premiere

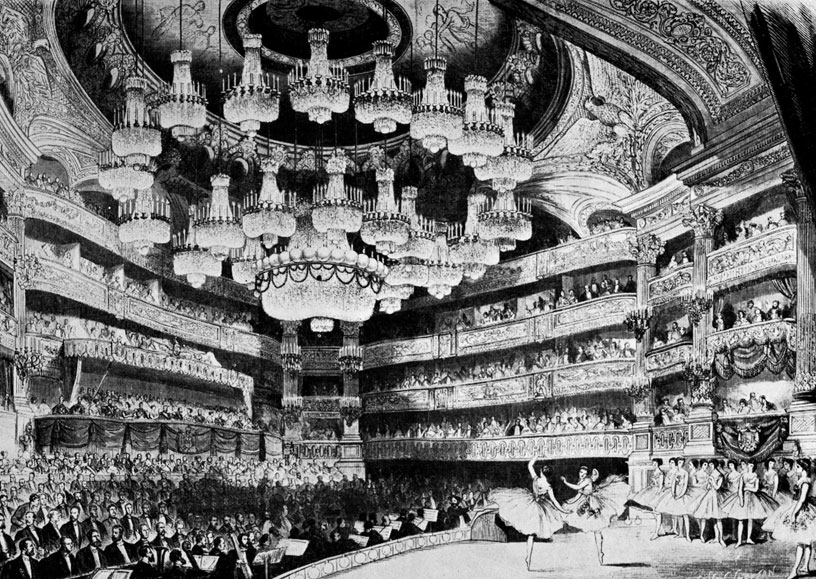

28 June 1841, Ballet du Théâtre de L’Académie Royale de Musique, Salle Le Peletier, Paris

Premiere Rachel Beaujean and Ricardo Bustamante’s version at Dutch National Ballet

10 February 2009, Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam

Sets, props, wigs and makeup, and lighting

Technical department of Dutch National Opera & Ballet

Production manager

Anu Viheriäranta

Stage managers

Wolfgang Tietze

Kees Prince

Production supervisor

Gerko Min

First carpenter

Jeroen Jaspers

Lighting managers

Angela Leuthold

Michel van Reijn

Lighting supervisor

Wijnand van der Horst

Follow spotters

Hein Hazenberg

Famke van der Marel

Panos Mitsopoulos

Carola Robert

Anton Shirkin

Marleen van Veen

Follow spotters coordinator

Ariane Kamminga

Sound engineers

Raymond Roggekamp

Juan Verdaguer

Props

Jurgen van Tiggelen

Assistant costume production

Michelle Cantwell

First dresser

Andrei Brejs

First make-up artist

Isabel Ahn

Orchestra manager

David Eijlander

Introductions

Lin van Ellinckhuijsen

Jacq. Algra

Duration

Circa two hours and fifteen minutes (including one interval)

Dutch National Ballet Orchestra

First violin

Sarah Oates, concertmaster

Kotaro Ishikawa

Suzanne Huynen

Robert Cekov

Jan Eelco Prins

Tinta Schmidt von Altenstadt

Majda Varga - Beijer

Casper Donker

Thirza van Driel

Leonie Kleiss

Anna Steenhuis

Arwen Terlou

Jenneke Tesselaar

Karolina Walarowska

Second violin

Arnieke Ehrlich

Yumi Goto

Willy Ebbens

Christiane Belt

Rebecca Gardiner

Bert van den Hoek

Feyona van Iersel

Jefke van Kerkwijk

Iina Laasio

Eva Lohse

Mirjam Michel

Rossi Ovtcharova

Viola

Naomi Peters

Arwen Salama - van der Burg

Maria Ferschtman

Joël Waterman

Simone van der Giessen

Lilian Haug

Gioia Kuipers

Audinga Musteikyte

Alexander Pavtchinskii

Ingerid Waleson

Giulia Wechsler

Cello

Artur Trajko

Lies Schrier

Willemiek Tavenier

Susanne Degerfors

Csaba Erdös

Wijnand Hulst

Melina Montes

Marjolein Nieuwenkamp

Double bass

Jean-Paul Everts

Annelies Hemmes

Lucía Mateo Calvo

Silvia Gallego Sánchez

Florian Lansink

Eudald Ribas

Flute

Karin Leutscher

Marie-Cécile de Wit

Oboe

Juan Esteban Mendoza Bisogni

Loli Martinez

Clarinet

Ina Hesse

Joris Wiener

Bassoon

Janet Morgan

Maud van Daal

Horn

Christiaan Beumer

Hendrik Marinus

Ward Assmann

Pablo Bajo Collados

Trumpet

David Pérez Sánchez

Erik Torrenga

Trombone

Bram Peeters

Wilco Kamminga

Jelle Koertshuis

Tuba

David Kutz

Timpani

Peter de Vries

Percussion

Richard Jansen

René Oussoren

Harp

Jet Sprenkels

Synopsis

The story of Giselle

Synopsis

Act 1

It is early morning in a village in a German wine region, in 1792. Hilarion returns from the hunt and hangs one of the birds he has shot, as a gift, on the house of Berthe and her daughter Giselle, who he adores. Slowly, the village stirs into life. The villagers gather on the green, before going to work in the vineyards.

When everyone has disappeared from view, Albrecht, the Count of Silesia, makes his entrance. In one of the cottages, he disguises himself as the villager Loys and knocks on Giselle’s door. The couple are madly in love, but the peasant girl does not know that Loys is actually a count.

The lovers are caught by Hilarion, who is jealous and suspicious. He gets into a fight with Albrecht, alias Loys, and when the latter appears to draw his sword, Hilarion is certain that something is not right.

The peasant girls and boys come back from the fields. Giselle introduces them to Loys and urges everyone to dance, but the dancing is interrupted by her mother. She reminds Giselle of her weak heart and begs her daughter to be careful. Because as legend has it, if Giselle should die, she could turn into a wili – the spirit of a girl who dies before her wedding day.

Once everyone has gone their way, Hilarion tries to find out who Loys is. He is interrupted by a hunting party that calls at the village. The Duke of Courland, his daughter Bathilde and their retinue are guests at Albrecht’s castle for the imminent betrothal of Bathilde and Albrecht, and are looking for a place to rest during the hunt. Berthe offers them refreshments, and Giselle cannot resist touching Bathilde’s beautiful clothes. The duke’s daughter is touched by the innocence and simplicity of the peasant girl. When she hears that Giselle is betrothed too, just like her, she gives her a necklace.

Hilarion discovers that the sword he found in Loys’s cottage bears the same coat of arms as the hunting horn. Now he knows for certain that Loys is not who he claims to be. When Giselle is crowned the queen of the harvest, Hilarion confronts her with the truth. Giselle does not want to hear his accusations, so Hilarion unmasks Albrecht in front of the hunting party. When Albrecht pretends he hardly knows the peasant girl, Giselle goes mad with grief. She tries to kill herself with Albrecht’s sword, but in the end, it is a broken heart that proves fatal.

Act 2

Hilarion is watching over Giselle’s grave. On the stroke of midnight, it seems as if he is surrounded by strange beings. Hilarion is frightened and wants to leave, but Myrtha, the queen of the wilis, bars his way. In despair, he flees into the forest.

One by one, the wilis are summoned by Myrtha. These spirits of brides who have died before their wedding day take their revenge on every man they meet in the dark, by making them dance to their death. They gather around Myrtha in a magic circle and welcome Giselle. The ritual is disturbed by the arrival of Albrecht. When he kneels by Giselle’s grave, her spirit appears at his side.

Meanwhile, the wilis have found and chased Hilarion, and are now forcing him to dance. Myrtha has no mercy whatsoever. Eventually, Hilarion falls from a rock in total exhaustion, following which the wilis go after their next victim, Albrecht. But Giselle protects him and begs Myrtha to leave her beloved alone.

Giselle urges Albrecht to seek protection by her grave, but he cannot resist following her. Myrtha then sees her chance and commands Albrecht to dance. Just as he reaches the point of exhaustion, dawn breaks, which is when the wilis lose their power and the sun’s warmth melts away their apparitions.

Giselle’s spirit fades and she can now rest in peace, freed from the power of Myrtha and her wilis. Albrecht remains behind alone. The adventurous, reckless youth he once was has made way for a reformed man, who has realised that nothing can surpass true, pure love.

Universal and timeless

Giselle through the ages

Universal and timeless

Giselle through the ages

The very first performances of Giselle, in Paris in 1841, were so successful that within five years the ballet had been presented in both Russia and America, as well as in many West-European cities. Over 180 years later, the work is still attracting full houses – not just for its magical and perfectly composed ‘white’ act, but also for its story of deception, madness, forgiveness and love that reaches beyond the grave.

Giselle was created in the first place thanks to the writer Théophile Gautier, one of the leading figures of French Romanticism and a fervent ballet enthusiast. Leafing though Heinrich Heine’s De l’Allemagne, Gautier came across a passage from a Slavic legend about the ‘wilis’. These spirits of brides who had died before their wedding day were said to rise from their graves at night and force male passers-by to dance to their death. Gautier was so fascinated by the macabre tale that he presented his idea for ‘Les Wilis, un ballet’ to librettist Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges, also referring to Victor Hugo’s Fantômes, about the fate of a Spanish girl who has such an irrepressible desire to dance that she dances till she dies.

Saint-Georges was immediately enthusiastic, and three days later he had prepared a scenario for Giselle ou Les Wilis, which incidentally was quite different to Gautier’s original notes. For instance, we know that Saint-Georges was responsible for the mad scene and for presenting the wilis as one uniform army of white spirits.

Resounding success

Besides his fascination with the wili legend, Gautier had another reason for wanting to create a ballet: his admiration for a young Italian ballerina, Carlotta Grisi. So it was a smart move by him and Saint-Georges to present their scenario first of all to Grisi’s teacher and lover Jules Perrot. Perrot was interested straight away and showed it to the composer Adolphe Adam, who was equally impressed and managed to persuade Léon Pillet, the director of the Paris Opéra, to produce Giselle. Pillet invited Jean Coralli, maître de ballet en chef at the Opéra, to choreograph the ballet. However, through the intercession of Gautier and Adam, all Grisi’s steps and variations were choreographed by Perrot. Not that Perrot received a penny for it, because he was not on the Opéra’s payroll, so originally his name did not even appear in the official credits.

The premiere of Giselle took place on 28 June 1841, at the Opéra, on the day that Grisi turned 22. Although there were some hitches in the first two performances (for example, the machinery for Giselle’s flight over the stage did not work), the ballet was a ‘succès éclatant’ right from the start. The magical, spectral atmosphere of the second act, in particular, was widely acclaimed.

The height of madness

The news of its success soon reached other countries, and over the space of a few years the ballet was performed in places like London, Vienna, Milan, Amsterdam, Brussels, Copenhagen, Stockholm, St Petersburg and various American cities. The London audiences were lucky enough to see both Carlotta Grisi and Fanny Elssler in the role of Giselle. Whereas Grisi excelled mainly in the second act, Elssler’s forte was the tragedy at the end of the first act. In other words, we have Elssler to thank for the heart-rending interpretation of the mad scene that so cruelly shakes up the lives of the villagers, and which has since formed one the greatest challenges of the narrative ballet repertoire for successive generations of ballerinas.

Over the years, the choreography of Giselle has changed many times, partly because it was handed down by word of mouth and partly because ballet masters and choreographers made cuts and additions to suit their own taste. In St Petersburg alone, versions followed one another in rapid succession, whereby the one created by Marius Petipa in 1887, for the Imperial Mariinsky Ballet, forms the basis for most of the ‘traditional’ Giselle productions that are performed today.

‘Tooverballet’

In the Netherlands, too, Giselle was an immediate success. At its first performance in 1844, the production was hailed as a new ‘Tooverballet’ (Magical Ballet). Like elsewhere in Western Europe, however, the big classical ballets disappeared from the repertoire at the end of the nineteenth century. It was not until 1955 that Giselle was presented in the Netherlands again, by Sonia Gaskell’s Nederlands Ballet (a forerunner of Dutch National Ballet), in a version by the Englishman Anton Dolin. Prior to the current production by Rachel Beaujean and Ricardo Bustamante, Dutch National Ballet had two versions of Giselle on the repertoire. The first, dating from 1966, was staged by the former Bolshoi ballerina Natalia Orlovskaya, and the second was by the Englishman Peter Wright, a specialist in reconstructing classical ballets. His production was on the company’s repertoire from 1977 to 1997, and was extremely popular with press and audiences alike.

Contemporary interpretations

New versions of Giselle are continually being produced. There are classical productions, which are often derived from Petipa’s version, as well as completely new, contemporary interpretations, for example situated in Louisiana just after the abolition of slavery or in Nazi-occupied Poland. Together, all these productions show that the themes of the ballet – deception, grief, madness, revenge, forgiveness and, above all, love that reaches beyond the grave – are universal and timeless.

The best-known contemporary Giselle is undoubtedly the one by Mats Ek from 1982. The Swedish choreographer portrays the heroine of the title as an uninhibited, sexually awakening teenager who is driven mad by the deceit of her urban ‘prince’ and ends up on a psychiatric ward, run by the strict senior nurse Myrtha.

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen

Translation: Susan Pond

‘Further than skin-deep’

Rachel Beaujean and Ricardo Bustamante about Giselle’s expressive power

‘Further than skin-deep’

Rachel Beaujean and Ricardo Bustamante about Giselle’s expressive power

The premiere of Dutch National Ballet’s new production of Giselle, by Rachel Beaujean and Ricardo Bustamante, took place fourteen years ago. The ballet has since had an international triumphal procession: from Colombia to China, it has been danced under a wide variety of circumstances. “That’s meant that the production has grown enormously and the dancers have put much more of their own stamp on it.”

A sky-high phone bill. That’s how the preparations for the new Giselle began, around fifteen years ago. Rachel Beaujean, associate artistic director of Dutch National Ballet, had daily phone calls with her ‘partner in crime’ Ricardo Bustamante, who is now head of the artistic staff of San Francisco Ballet. “At six in the evening, because of the time difference.”

The pair talked for hours about the libretto, the order of the scenes, the interpretation of the characters and, most of all, the meaning of the ballet. “Because”, says Bustamante, “Giselle is only as good as the spirit you manage to give it.” Beaujean adds, “For us, the ballet is not primarily about the steps, but about the emotion and intensity with which the choreography is danced. Giselle has to go further than skin-deep.” Bustamante explains, “The second act, in particular, has such an ethereal beauty that even people who’ve never seen a ballet before can be totally hypnotised by it.” Beaujean says, “The choreography and the composition of the dances is phenomenal. If it’s presented well, Giselle has no sell-by date. It’s timeless; just like the Night Watch.”

True love

Both artists have earned their spurs in the ballet. Beaujean was once a wonderful, commanding Myrtha, and Bustamante was an exceptional Albrecht, partnering prima ballerinas like Carla Fracci and Alessandra Ferri. Beaujean says, “I particularly wanted to embark on this adventure with a seasoned Giselle or Albrecht; someone who’d had thorough first-hand experience of the ballet. Ricardo learned his role from Mikhail Baryshnikov, and worked on it later with Rudolf Nureyev and Vladimir Vasiliev as well.”

Right from the start, Beaujean and Bustamante knew that true, pure love would be paramount in their production. Bustamante says, “There are dancers who portray Albrecht as a Casanova – a flirt who simply toys with Giselle’s emotions.” “But”, says Beaujean, “we think a story that’s so dramatic can’t be based just on someone playing a game. In our vision, Albrecht is genuinely in love with her, so we wanted to portray all the emotions that entails.”

They were also in total agreement about the role of Giselle. “She has to be a woman of flesh and blood; a woman who’s also capable of forgiveness after her death. And not just simply a spectre that rises from her grave.”

Meaningful to today’s audiences

Beaujean and Bustamante stress that their production is not ‘a modern re-creation’ of the nineteenth-century ballet, but above all ‘a product of choices and taste’. Bustamante says, “Our main principle was to revitalise Giselle in a way that was attractive and meaningful to a twenty-first-century audience. In our view, you have to be really swept up in the drama.”

That led to some necessary interventions, mostly in the first act of the ballet, ranging from the revival of some mime scenes, which had previously been lost, to the addition of new dances, such as a pas de quatre, a variation for Albrecht and a grape-treading dance. Beaujean says, “The additions were subjected to heavy criticism here and there, at the premiere in 2009. But already at the revival in 2012, nobody was talking about them any more. Albrecht’s role is now much more equal to Giselle’s. And the grape-treading dance provides a breath of change; a sort of comic relief.”

The fact remains that the second act – the pièce de résistance of Giselle – is more abstract, so naturally has a more modern feel to it, whereas the ‘peasant’ first act is much more difficult to make ‘relatable’ to a contemporary audience. “But”, emphasises Beaujean, “without that earthy first act, the second act would never be as beautifully ethereal.”

Oxygen cylinders

Since 2009, the new production of Giselle has toured to Bogotá in Colombia, Izmir in Turkey, Madrid in Spain, Göteborg in Sweden and the Chinese cities of Shanghai, Beijing and Hangzhou. Beaujean says, “For Ricardo, the performances in Colombia, his homeland, were particularly special. It was as if he was taking his ‘baby’ home for the first time.”

Bogotá is situated at an altitude of 2600 metres, so the dancers had a lot of trouble with lack of oxygen. “We danced with oxygen cylinders in the wings. They were absolutely necessary for Albrecht and Myrtha, in particular. Halfway through their variations, they really hit the wall – the feeling that you just can’t go on dancing.”

In Beijing, Dutch National Ballet’s Giselle was coupled with a Dutch trade mission. Beaujean says, “The mayor of Amsterdam at the time, Van der Laan, saw the ballet for the first time, and he confessed to wiping away the odd tear or two.”

For the dancers, it was very special to experience so many cultural differences, says Beaujean. “In China, people are very hungry for Western culture, after being deprived of it for so long. Suddenly, you get a whole array of Chinese people on stage, all fanatically taking photos of the scenery. And the audiences there are very focused on dance technique, with everyone clapping when Albrecht does a double tour en l’air. Whereas in Colombia, we noticed that the ballet appeals more to the spiritual, religious nature of the population. The idea that people return as spirits after their death is something that everyone there finds very normal, and people attach great value to forgiveness, whether from God or from a loved one.”

Self-confidence

All these experiences have left their mark on the production and added vitality to it, says Beaujean. “We’ve gone through so much and performed under such a wide variety of circumstances: in tiny theatres with fewer wilis (due to lack of space), in the freezing cold, during a flash mob in a shopping centre, lacking in oxygen and, in China, under a thick blanket of smog, which did produce”, she jokes, “a wonderful mist in the second act.”

Due to all the tours, the dancers have also danced the ballet far more often than usual. Beaujean says, “In the Netherlands, a full-length production comes back every four years on average, but Giselle has been performed much more frequently since 2009 – not counting the corona period. So the dancers have been able to put much more of their own stamp on the roles. The ballet has ‘sunk in’, as it were, in all its details and nuances.”

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen

Translation: Susan Pond

Ethereal, timeless beauty

Origins of the ‘ballet blanc’

Ethereal, timeless beauty

Origins of the ‘ballet blanc’

Sylphs, phantoms, shades, fairies, nymphs and dryads: from the 1830’s they filled the ballet stages. Inspired by the ideas of Romanticism, supernatural beings transported the audience to other worlds, in‘white acts’. This led to a series of wonderful choreographic works that still touch the heart and delight the eye.

On hearing the term ‘white act’, those who are not fervent ballet-goers may not directly envisage a large corps de ballet of women in white tutus. Even if you google the term, you still get many other assorted hits besides the odd photo of the famous white act from Giselle. The main role in this act is taken by the ‘wilis’: spirits of brides who have died before their wedding day and who rise from their graves at night to take revenge on every man that passes by.

Literary sources

For classical ballet diehards, however, the white acts – originally known as ‘ballets blanc’ – often form the mainstay of their passion. The ‘white ballets’ originated in France in the first half of the nineteenth century. It was the era of Romanticism, which revolved around concepts like the duality between the physical (the body) and the spiritual (the soul), and the idea that a higher truth was concealed in all earthly phenomena. Many Romantic ballets are based on literary sources. For example, one of the leading writers of French Romanticism, Théophile Gautier, laid the foundations for Giselle, inspired by a Slavic legend about the wilis in Heinrich Heine’s De l’Allemagne.

Dream scenes

A work that is often cited as a forerunner of the ‘ballet blanc’ is the ‘Dance of the Dead Nuns’, which formed part of Giacomo Meyerbeer’s opera Robert le Diable from 1831, for which Filippo Taglioni did the choreography, with his daughter Marie in the leading role.

One year later, this Marie Taglioni danced the main role in La Sylphide (still on Dutch National Ballet’s repertoire), which is about the Scottish farmer’s son James, who is torn between the love of his fiancée Effie and his longing for another, higher world, symbolised by a wood nymph (sylphide) and her ‘ethereal sisters’. It was the first time a title role had been danced on pointe throughout a whole ballet, and in the dream scenes of the ballet a large female corps de ballet of sylphides made formations, swathed in long white tutus – which gave rise to the term ‘ballet blanc’.

New impulse

Many famous white acts were to follow, the best-known and purest examples being the second act of Giselle (1841), the ‘Kingdom of the Shades’ in La Bayadère (1877) and the second and fourth acts of Swan Lake (1877/1895). In the latter two ballets, the long skirts were replaced by short tutus in later productions. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the choreographer Michel Fokine gave the genre a new impulse in his Chopiniana (1907) – later rechristened Les Sylphides – by removing the storyline from the ‘ballet blanc’, and so in effect creating the first pure music ballet.

Night Watch

The fact that many of the big nineteenth-century ballets have stood the test of time and are still acclaimed all over the world is often primarily thanks to their white acts – breathtaking fragments of pure classical dance. Rachel Beaujean, who created Dutch National Ballet’s new production of Giselle (along with Ricardo Bustamante) in 2009, explains, “The white act of Giselle has such ethereal beauty, and the composition of the dances is absolutely phenomenal. This means the ballet has no sell-by date. It's timeless; just like the Night Watch.” And former prima ballerina Natalia Makarova (who staged her version of La Bayadère for Dutch National Ballet) calls the ‘Kingdom of the Shades’ in La Bayadère “the greatest choreography ever created for a corps de ballet, in its formalism, harmony and precision, and in the crystalline execution it requires.”

Virtual reality

No wonder that the ‘ballet blanc’ still inspired choreographers in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries – and will continue to do so. New traditional versions of the aforementioned ballets are still being produced, as well as contemporary, distinctive interpretations. One of those traditional versions is the production of Swan Lake created by the Englishman Derek Deane for English National Ballet, which has no fewer than sixty swans instead of the usual twenty-four (it will be presented again in 2024 at the Royal Albert Hall in London, and was recently staged at Theater Carré – in an adaptation with fewer swans). Deane says, “The corps de ballet of swans is even more important to me than the ballerina. They magnify her pain, as it were, like ripples on a lake.” The British choreographer Matthew Bourne chose to create an all-male Swan Lake instead and, like him, the British-Bengali choreographer Akram Khan also preserves the concept of the ‘ballet blanc’ in his contemporary Giselle, even though the wilis in his production are ‘spirits of factory workers who seek revenge for all the wrongs done to them in life’. In addition, there are now ice-skating, musical and hiphop versions of many ballet classics that usually include a variant on the ‘ballet blanc’, and in his virtual reality production Night Fall (from 2016), choreographer and former Dutch National Ballet dancer Peter Leung even gives viewers the sense of taking part in a ‘ballet blanc’ themselves.

Text: Astrid van Leeuwen

Translation: Susan Pond

The wilis in Giselle: deceived and vengeful

That gives me the willies! According to several sources, this expression could well be derived from the story of the Wilis in Giselle. The French writer Théophile Gautier was inspired for the original libretto of the 1841 ballet by an old Slavic legend about the spirits of deceived maidens who died before their wedding day, which he had read in Heinrich Heine’s De l‘Allemagne (1835). The legend goes that these ‘wilis’ haunted the woods and surrounding paths at night, where they took revenge on young men, ensnaring them and making them dance to death. Incidentally, the legend and the exact name of the spirits assume various forms in East-European folklore, which vary per region. Sometimes it is about girls who were cursed by God, and sometimes about girls who died unbaptised, but often it concerns young women who were betrayed by their lover before their wedding day. Various stories are also in circulation about the origins of the word ‘wili’, but the most probable explanation is that it comes from the Serbo-Croat word ‘vila’ (pronounced ‘wila’), meaning wood nymph, spirit or fabulous creature. In contrast to fairies, who are born as nature spirits, these ‘vile’ only assume the form of spirits after their death, and – unlike fairies – they are known for their cruelty to living, mortal people.

Nowadays, too, the legend of the wilis, and variations on it, are still a source of inspiration for writers and other artists. They even seem to appear in some of the Harry Potter books by J.K. Rowling. In Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, the British writer introduces the ‘veela’ for the first time: “the most beautiful women Harry had ever seen, with skin that shone moon-bright”. These ‘veela’ hypnotised men through their appearance and their dancing, forcing them to act in the most impulsive and ridiculous way. “And”, writes Rowling, “if they stopped dancing, terrible things would happen.”

‘The poor creatures do not lie easy in their tomb. In their stifled hearts, in their lifeless feet, they are caught up in a passion for the dance that never was sated in life. At midnight, they glide forth to gather on the high road, and alackaday to any youth who comes upon them.’

Excerpt from Heinrich Heine’s De l’Allemagne

Image: La légende des willis, a work by nineteenth-century French painter Hugues Merle

Leitmotifs as musical guides

Leitmotifs as musical guides

The music of Giselle

Leitmotifs, profound emotions and musical craftsmanship: the music of Giselle guides the audience smoothly through the story and supplements the choreography to perfection. The French composer Adolphe Adam (1803-1856) took just three weeks to write the score, making use of musical contrivances to tell a romantic and tragic story.

Adolphe Adam was a composer with a passionate focus on the composition of music for theatre, resulting in an oeuvre that comprises more than eighty works for opera, ballet and vaudeville, among other art forms. Although Giselle is nowadays one of the most popular Romantic ballets, Adam was known during his lifetime mainly for the 39 operas and operettas he composed. And today most people probably know him for the world-famous Christmas classic O Holy Night (called Cantique de Noël in French).

Adam’s versatile musical oeuvre and dedication to art formed a firm basis for his masterpiece Giselle. Adam wrote uncomplicated yet effective melodies, with simple harmonies that were easily understood by the dancers of his day. His extensive use of leitmotifs in Giselle – recurring musical themes that are associated with characters, objects or emotions – is undoubtedly a contributing factor to the ballet’s success and lasting popularity. It was not without reason that Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky took inspiration from the leitmotifs in Giselle before starting on his first ballet composition, Swan Lake, between 1875 and 1876.

Leitmotifs as emotional puzzle pieces

As the narrative of Giselle unfolds, Albrecht’s entrance in the first act not only gets the story going, but also introduces the leitmotif specific to this interesting character: a dynamic and exciting theme. the liveliness and vitality of the theme paints a portrait of an adventurous and self-assured young man in the prime of his life. The motif is often associated with his romantic aspirations and his passion for Giselle, the woman he falls in love with. The crescendo outbursts and driving tempo heard in the music make the listener feel Albrecht’s excitement and determination.

Two important themes are introduced straight away when Giselle comes on stage. The first is played in 6/8 time – a carefree, ‘skipping’ rhythm that listeners usually associate with playful childhood. The innocence and naivety of the theme portray Giselle as a vulnerable young woman, who has only just turned the corner into adulthood. The second theme is the love theme of Giselle and Albrecht, which we hear in their meeting in the famous ‘he loves me, he loves me not’ scene. It is a gentle theme consisting of three tones in a question and answer structure. In this motif, Giselle asks if Albrecht truly loves her: a tender melody that reflects her vulnerability. The answer to this question comes from Albrecht, and it shows his passion for, and devotion to Giselle. This question and answer structure symbolises the mutual attraction between the two protagonists.

In the second act, following the tragic death of Giselle, Albrecht’s theme undergoes a dramatic change. When he brings flowers to Giselle’s grave, the theme becomes melancholic, sombre and imbued with sorrow and regret. This change is expressed in an emotional solo for cello in a minor key. Giselle’s leitmotif remains recognisable and unchanged in the second act, symbolising her immortality and her constant purity. Although Giselle has physically died and become a wili, her spirit and her love of Albrecht are still present. This is reflected musically by the use of her leitmotif, which continues to resonate, albeit with a melancholy and ghostly quality that befits her supernatural state.

Ill-fated Hilarion

In Giselle, we enter the heart of a complex love triangle. Besides the central figures of Giselle and Albrecht, there is a third character who makes his mark on this romantic drama: Hilarion. As Giselle’s admirer, Hilarion adds an extra layer of intrigue to the story. His leitmotif in the music illustrates his tenacity and deep-rooted jealousy, and underlines the strong emotions and conflicts that unfold in his endeavour to win over Giselle, in spite of her love for Albrecht. Hilarion’s motif is always heard when he comes on stage. It bears a strong resemblance to the famous fate theme of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, and is a definite nod to the disastrous scenario that awaits the gamekeeper and admirer of Giselle in the second act.

Whereas the music for the first act suggests a sunny day in a village, the music for the second act reinforces the atmosphere of the nighttime scenes in the forest. The imminent tragedy is already heralded in the first act, when Giselle’s mother Berthe warns her of the inevitable fate that awaits her. The ominous music illustrates the impending disaster of her death and introduces the theme that characterises the ghostly wilis later on, in the second act. The wilis’ leitmotif is characterised by dark sounds that reflect their supernatural quality and the threat they pose to the male characters. The theme is performed mainly by the strings, which play sombre, protracted notes with superb control and thus create a spine-tingling atmosphere. Even more suspense is added to the sound dimension using tremolo, a technique whereby the string is bowed rapidly and repeatedly.

Entrancing narrator

The masterly use of leitmotifs in Giselle illustrates how music has the power to reinforce and link up emotions, characters and storylines. Adolphe Adam’s well-thought-out application of these musical themes creates a profound and compelling experience for the audience. Each leitmotif functions as an emotional point of reference that guides the spectator through the complex web of love, jealousy, revenge and forgiveness. This artistic use of leitmotifs is one of the factors that make Giselle a timeless, poignant classic, whereby the music functions as an entrancing narrator and brings the story to life.

Text: Stan Schreurs

Translation: Susan Pond

Programmaboek

Become a Friend of Dutch National Ballet

As a Friend you support the dancers and makers of Dutch National Ballet. You are indispensable to them and we are happy to do something in return. For Ballet Friends we organize exclusive activities behind the scenes. You will receive the Friends magazine from us and you will receive priority when ordering tickets.